“WHO WILL COMMAND THIS OPERATION?”

Ike Takes On OVERLORD

by Joseph Balkoski

Posted January 20, 2014

The name of Dwight Eisenhower will forever be intertwined with the history of D-Day. But for most of 1943, virtually no one, including President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill, considered Ike the leading candidate to command that momentous operation. Instead, insiders judged the British Army’s chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir Alan Brooke, or the U.S. Army chief of staff, George C. Marshall, the best men for the job. Sooner or later Churchill and Roosevelt would have to pick one of those two astute soldiers for the post that was considered so vital that it already had been assigned the lofty title of “supreme commander.”

Even when the Combined Chiefs of Staff accepted Lt. Gen. Frederick Morgan’s OVERLORD plan at the August 1943 Quebec conference as the Allies’ foremost military operation of 1944, the supreme commander for whom Morgan was supposed to be working had not been named. By that summer, however, Churchill remarked that the man to whom he had thrice promised the slot, Brooke, would no longer be acceptable to the Americans because of “the very great preponderance of American troops that would be employed after the original landing.” It would have to be an American, avowed the prime minister. Churchill recalled that Brooke “bore the great disappointment with soldierly dignity”; Brooke, however, noted that “the blow . . . took me several months to recover from.”

Marshall’s selection as supreme commander seemed so inevitable that the general’s military secretary, Col. Frank McCarthy—future producer of the film Patton—dispatched an executive desk across the Atlantic for use by Marshall once he assumed command. Secretary of War Henry Stimson urged Roosevelt to anoint Marshall, describing the general as “a towering eminence. . . . [He] is the man that most surely can now by his character and skill furnish the military leadership which is necessary to bring our two nations together in confident joint action in this great operation.” Marshall, however, steadfastly refrained from influencing FDR on his own behalf, despite Stimson’s assertion that the general, in a moment of candor, had admitted, “Any soldier would prefer a field command.”

Snapped shortly after the close of World War II, this photograph of Dwight Eisenhower clearly reveals that the burden of wartime high command has been lifted from his shoulders. He is wearing the new five-star “general of the army” rank on his “Ike” jacket. (Eisenhower Presidential Library)

By the time Churchill, Roosevelt, and their retinues arrived in Tehran on November 27, 1943, to join Joseph Stalin in the first of the war’s three-power summits, a supreme commander had still not been named despite OVERLORD’s scheduled commencement in five months. For years Stalin had clamored for the Allies to open a second front in western Europe to draw German units away from the east. But at their second plenary meeting on November 29, Stalin inquired, “Who will be the commander in this Operation OVERLORD?” According to the transcript, “The president and prime minister interpolated this was not yet decided.” An incredulous Stalin retorted, “Then nothing will come of these operations.”

Roosevelt had once affirmed, “I want George [Marshall] to be the Pershing of the Second World War.” But according to Stimson, to whom FDR related the account: “[Roosevelt] tried to get Marshall to tell him whether he preferred to hold the command of OVERLORD . . . or whether he preferred to remain as chief of staff. . . . He said that Marshall stubbornly refused, saying that was for the president to decide and that he, Marshall, would do with equal cheerfulness whatever one he was selected for.”

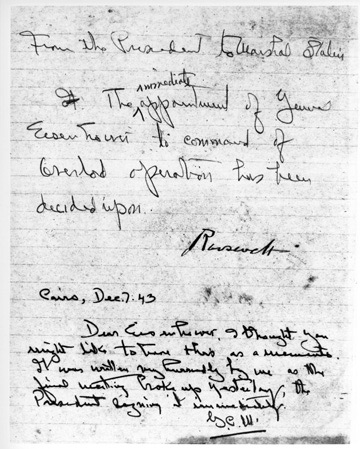

On the way home from Tehran, the Anglo-American delegations stopped in Cairo for more talks. On the evening of December 6, in FDR’s beautifully furnished villa, featuring an exquisite garden in full view of the Pyramids, the president called Marshall into his suite. No stenographers were present, just the two great men, who would presently emerge with stunning news. Roosevelt asked Marshall to grab paper and pencil and jot down a few words as he dictated a letter to Stalin. Cast in the role of an ordinary secretary, the four-star general scribbled earnestly as FDR pronounced, “The immediate appointment of General Eisenhower to the command of OVERLORD has been decided upon.”

Finally, OVERLORD had its supreme commander. An unknown Regular Army colonel three years in the past, Eisenhower had soared into the most important American field command of World War II. Marshall—still Ike’s boss—ordered Eisenhower to return to the States for a few weeks of rest, and Ike did exactly that, dropping in on his son at West Point, flying out to Kansas to visit his mother and brothers, relaxing for a few days at the grand Greenbriar Hotel in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia.

At a January 1944 meeting with Roosevelt at the White House, FDR asked, “Ike, do you like the title of Supreme Commander?” Eisenhower replied: “I like the title, Mr. President. It has the ring of importance—something like ‘Sultan.’”

President Roosevelt dictated this message to General George C. Marshall in Cairo in December 1943. “From the President to Marshal Stalin: The immediate appointment of General Eisenhower to command of Overlord operation has been decided upon.” Below that is Marshall’s personal note to Eisenhower, to whom he presented the message as a memento. (Eisenhower Presidential Library)

Joseph Balkoski, who served for many years as the command historian for the Maryland National Guard and the U.S. Army’s 29th Infantry Division, is the author of Omaha Beach and Utah Beach, a two-volume account of the American involvement in the D-Day invasion. More than twenty-five years ago, he began work on a five-volume series about the 29th Division’s service in World War II. The first book in that series, Beyond the Beachhead, was published in 1989 and has been in print continuously ever since. The fourth volume, Our Tortured Souls, was published in 2013. Joe currently runs the 29th Division’s archives and museum in Baltimore, Maryland. He conducts battlefield staff rides in the United States and Europe for current U.S. Army soldiers as part of their military training and was recently recognized by USA Today as “the top living D-Day historian.”

comments powered by Disqus