Author Q & A

(The following interview was conducted by the National World War II Museum in New Orleans and published in the Museum’s spring 2013 newsletter.)

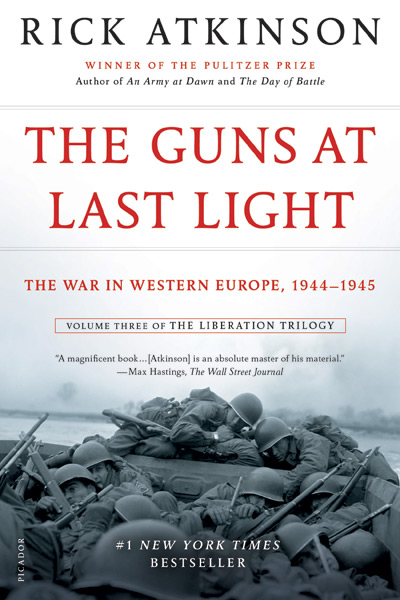

The Guns at Last Light, Rick Atkinson’s long-awaited third and final book in his “Liberation Trilogy,” about the US military in Europe in World War II, is being released to the public on May 14th. Rick has long been a friend and supporter of the Museum and we are honored that he and his publisher have selected the Museum to host his official book release event on Wednesday, May 8, 2013 – VE-Day!

As we approach this much anticipated event, we wanted to ask Rick some questions and share his answers with our members.

WWII Museum: Congratulations on the upcoming release of The Guns at Last Light! Could you tell us where the book picks up, what is covered and where you conclude the final volume?

Rick: Thanks so much to The National WWII Museum for supporting this project. I feel that we’ve come of age together: the Museum opened in 2000, shortly before the first volume of my trilogy was published.

The Guns at Last Light opens on May 15, 1944, at St. Paul’s School in London, where Eisenhower, Montgomery, Churchill, Patton, Bradley, and several dozen other American and British commanders gather to review the final plan for the invasion of Normandy. It’s a wonderfully cinematic scene, full of color and high drama. For the next twelve chapters we live and die with those determined to obliterate the Third Reich, at places like Omaha Beach, St. Lô, Hill 314, Falaise, the Hürtgen Forest, Antwerp, Nijmegen, Arnhem, and on through the Bulge, the crossing of the Rhine, the encirclement of the Ruhr, and the final drive across the Elbe through V-E Day on May 8, 1945. As in An Army at Dawn and The Day of Battle, we periodically shift from a tactical, foxhole view of the battlefield to the wider aperture of operational and strategic perspectives; much of chapter 7 is set in Malta and Yalta, for instance, in the company of Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin, and the Allied high command. And we often peek in on the other side of the hill, to understand what the Germans are doing.

I also recount at some length the invasion of southern France in mid-August 1944, as well as the subsequent drive up the Rhône valley and the Franco-American lunge through the Vosges Mountains to capture Strasbourg and reach the Rhine, four months before other Allied forces arrive on the river. That controversial campaign in southern France is unknown to many Americans, and it’s an important part of the liberation of Europe.

WWII Museum: Tell us something about the Normandy Campaign that we don’t know.

Rick: The Americans secretly considered invading France by digging a tunnel under the English Channel; engineers calculated that it would take 15,000 men a year to excavate 55,000 tons of spoil, but they couldn’t figure out how to avoid having the entire German Seventh Army waiting for the first tunneler to emerge. Did you know that? The U.S. military alone stockpiled 160,000 tons of chemical munitions for potential use in Europe and the Mediterranean; I found Eisenhower’s target lists for phosgene and mustard gas attacks, including a plan described as “involving risk to civilians” because it required spattering deadly chemicals from St. Lô to Le Mans, as well as on rail junctions and enemy garrisons at Avranches, Versailles, and elsewhere. Did you know that Allied planners worried about German planes dropping rats infected with bubonic plague over English cities? Or that Geiger counters were secretly stockpiled in London in case the Germans used “radioactive poisons?” Did you know that the U.S. military’s need for draftees had become so pressing by 1944 that a man could be inducted if had no teeth—the original standard had been at least twelve—or was missing an eye, both external ears, a thumb, a great toe, or three fingers on either hand, including his trigger finger? I could go on and on.

WWII Museum: Your book covers both Allied failures and successes. What do you think was the greatest failure of the Allies in the last year of the war in Europe?

Rick: Probably the two greatest tactical missteps were the failure to take the sea approaches to Antwerp when that port was captured in early September 1944, and Operation MARKET GARDEN, the attempt to outflank German defenses through Holland. The first was a sin of omission, which cost the Allies use of a large, vitally needed port in northern Europe for nearly three months; the second was a sin of commission, as daft as it was bold. I also think that Eisenhower’s refusal to allow Sixth Army Group to cross the upper Rhine in late November of 1944 was probably a mistake, although I understand his reasoning. And failure to detect German preparations for the Ardennes counteroffensive was the greatest intelligence failure of the European campaign. On the other hand, I’m persuaded that Eisenhower’s broad-front operational concept in attacking Germany was sensible, in contrast to the narrower, single-prong attack advocated by Field Marshal Montgomery.

I’m generally forgiving of certain politico-military “failures” that have been denounced by some skeptics for more than six decades. For example, I don’t believe that President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill at Yalta could have negotiated a much more rigorous deal to thwart Soviet dominion in Eastern Europe. And given battlefield realities in the spring of 1945, Eisenhower’s decision to forego an attack on Berlin—leaving that bloody task to the Red Army—was correct in my view. As it was, nearly 11,000 American soldiers died in Europe in April 1945, almost as many as in the invasion month of June 1944.

WWII Museum: With so many topics and so much content to cover (D-Day, Paris, “Market-Garden,” The Bulge, V-E Day) did you find it easier or more difficult to tell this story?

Rick: There’s no doubt that there’s a lot of story to pack into one volume. A decade ago, I had assumed that in moving from North Africa to Italy the archival sources and secondary material would increase by an order of magnitude, tenfold, and that there would be a comparable increase in jumping from Italy to Western Europe. In fact, I think the increase for Europe is considerably greater, perhaps two orders of magnitude, or a hundredfold. It was a challenge, but every author makes choices about what and who to include or exclude; that’s part of the writer’s art. I feel confident that The Guns at Last Light is comprehensive without being exhaustive. World War II is bottomless; there will always be more to write about.

I should mention that this book not only has eighty wonderful photos, some of which I’ve never seen elsewhere, but also twenty-nine original maps drawn by master cartographer Gene Thorp, who drew the maps for the previous volumes.

WWII Museum: Your trilogy really brings personalities of the war to life, both for senior officers and GIs. Tell us about a couple of favorite individuals you’ve written about; both those who are famous and those lesser known individuals.

Rick: I’ve traveled for nearly fifteen years and through three volumes with a platoon of personalities to whom I’m deeply attached, not just Eisenhower, Patton, Montgomery, Bradley, Churchill, Brooke, and their ilk, but the likes of Ted Roosevelt and Lucian Truscott, who are less known to many readers. The narrative writer’s true calling is to bring such folk back from the dead. I try to do that not only for soldiers of all ranks and across various nationalities, but for other personalities who help propel the story, including gifted journalists like Alan Moorehead, Ernie Pyle, Martha Gellhorn, Robert Capa, A.J. Liebling, Eric Sevareid, and Osmar White.

In The Guns at Last Light, a number of arresting new personalities come on stage with that Franco-American army group in southern France, including Jacob Devers, Alexander Patch, and Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, the flamboyant French First Army commander who is beyond the inventive power of any novelist. I also get to pick up stories from the earlier volumes. For example, we’ve last seen Lieutenant Colonel John K. Waters, a fine officer who happens to be Patton’s son-in-law, being hustled off to a German prison camp after his capture on the first morning of the Kasserine Pass debacle in Tunisia. Now we’ll be reunited with him as a consequence of Patton’s hare-brained raid on the camp at Hammelburg, in upper Bavaria, during which Waters is shot and severely wounded. Through the generosity of his son, I have Colonel Waters’s diary and camp logs to draw from, giving us his view for the first time, as well as an absolutely mesmerizing photo of him.

WWII Museum: What surprised you the most in your research and writing that our readers would find of interest?

Rick: The archival trove is richer and vaster than I’d ever dreamed. One scholar has calculated that the US Army records alone for World War II weigh 17,000 tons—that’s the paper trail of just one service from one country. So for an archive rat like me, the opportunities to make new discoveries and then to paint in vivid, textured hues are boundless. The greatest surprises always involve human nature. The degree of Anglophobia among senior U.S. Army officers continues to confound me. The pettiness, back-biting, and puerile insecurity of various players ought not surprise us—everyone has feet of clay, after all—and yet misbehavior is positively Homeric in the European war. At one point on the eve of the Bulge, when various personalities are struggling with the lesser angels of their nature, I write, “War, that merciless revealer of character, uncloaked these men as precisely as a prism flays open a beam of light to reveal the spectrum. Here they were, disclosed, exposed, made known.” That’s what appeals to me most in writing about men at war: humanity for good and for ill can be seen at every turn.

WWII Museum: Take us behind the scenes. We assume that much of what a writer sends to his editor, unfortunately, doesn’t make it into the finished product. Tell us one of your favorite stories or subjects that had to be left on the editing desk.

Rick: To be honest, very little of what I write in the initial draft ends up in the trash bin. Perhaps I should be more exclusionary, but my feeling is that if the book is bloated when it goes off to New York for editing, I’ve fallen short in conceiving and writing the thing. Having said that, sure, there are many events that I’ve had to truncate or omit. The trilogy has very little about the Pacific or the Eastern Front, for example. In ending The Day of Battle with the fall of Rome in June 1944, I exclude the entire last year of the campaign in Italy from volume 2, and volume 3 returns to Italy only for the staging of the invasion of southern France. There are many acts of valor, both by individuals and by small units, that of necessity I exclude in The Guns at Last Light. I regret that, but I also recognize that it’s already a long book.

WWII Museum: Is there a story, or a “hidden gem” that you uncovered, whether you were able to include it in one of your books or not, that has really stuck with you?

Rick: Even amid the clash of army groups, my eye is always drawn to the small, particular catastrophe that somehow illuminates the larger tragedy. The death of General Sandy Patch’s son, Mac, still sears me. I tell that story using the general’s letters to his wife, and it’s unspeakably heartbreaking; even while continuing to do his duty as Seventh Army commander, General Patch never got over it. How could you? I recount the suicide of Rear Admiral Don P. Moon, who had commanded the naval forces at Utah Beach, and blew his brains out shortly before the invasion of southern France; the stress unhinged him, and the note he left for his wife and four children is haunting. Having been with Ted Roosevelt through two previous volumes, I hated, just hated, to say goodbye to him in Normandy. I spent considerable time researching the new C-46 transport airplanes used for the airborne drop of Operation VARSITY PLUNDER in March 1945; for misbegotten reasons of cost and weight, self-sealing fuel tanks were not used in those C-46s, and the result was catastrophic. I still hear men screaming in those burning planes. I also did a lot of rummaging through the archives to find the full story of the “pozit” fuze, the highly secret invention that allowed much more accurate field artillery and anti-aircraft gunnery. On a quite different subject, I found a detailed narrative written by the Georgia mortician who prepared Franklin Roosevelt’s body for burial after the president died at Warm Springs in April 1945—the document is as powerful and moving as it is clinical.

WWII Museum: Your book will be released on May 14th but you have actually been done with the writing process for some time. Now that you have had some distance between the three books can you tell us which of the 3 is your favorite?

Rick: Every parent knows better than to single out one child for preference over another, and authors have a similar reluctance to suggest that one book is more special than another, particularly when three volumes are as closely intertwined as those in my trilogy. Having said that, I just re-read volume 1, An Army at Dawn, for the first time in eight or nine years, and I find a poignancy in the first faltering efforts by American troops to take the fight to the enemy in North Africa. For much of that campaign, the battles are company- or battalion-sized, and thus there’s a human scale to the story that I still find arresting. By the way, a weird nostalgia for the “simplicity” of North Africa was not uncommon among Africa veterans who later found themselves in Italy and Western Europe.

As for volume 2, the natural tensions in the Italian campaign make for powerful story-telling—tensions between characters, but also over whether waging war in Italy made any sense strategically. General Mark Clark is often dismissed as an egocentric mediocrity, but I find him much more nuanced and compelling than that. He carries much of the book.

And volume 3 certainly brings a sense of fulfillment—because of the Allied victory of course, and, on a personal level, because of a conviction that this triptych of mine really does fit together. I have long argued that a 21st century reader can’t really understand the decisive final year in northwest Europe without knowing what preceded it in the Mediterranean. Certainly writing about the European war as a saga that begins in Africa and Italy has given me a deeper sense of what happened and why. It’s one grand epic.

WWII Museum: Why do you think WWII is a subject that still fascinates the American public, 70 years after the fact, and that it is important The National WWII Museum shares that story?

Rick: The Second World War is the greatest self-inflicted catastrophe in human history—60 million dead, one life snuffed out every three seconds for six years. As John Updike once wrote, it’s the 20th century’s central myth, “a tale of Troy whose angles are infinite and whose central figures never fail to amaze us with their size, their theatricality, their sweep.” The war’s legacy is so profound and ubiquitous that we almost don’t recognize those influences, from the shape of the geopolitical map today to the way the war influenced our national evolution on racial and gender equality. I believe the war will transfix people a millennium from now. It’s that powerful and compelling.

Of more than 16 million American veterans of World War II, fewer than 2 million remain alive. When we contemplate what is lost to us culturally as they slip into the shadows at the rate of 800 a day, foremost perhaps is the ability to bear witness, to tell the story first-hand, to attest with authenticity and authority, why they fought, suffered, and died. For all the stories told and retold, countless others will now go untold. So as the primary storytellers die off, it’s important for their survivors—for us—to sustain the story, to keep it a vivid narrative that lives and breathes, rather than something desiccated, rapidly receding into the past with ever diminishing power to stir us. The National World War II Museum has a pivotal role in that profound task. For the Museum, this has become a calling, and we’re a better country and a richer culture for it.

WWII Museum: Thank you Rick, the Museum is greatly looking forward to hosting your book release party on May 8th!

Rick: I can’t wait. Thanks again to the Museum and its superb staff for supporting me, but more important, for helping to preserve our common heritage.

We hope that many of our friends and members from around the country come down to New Orleans for the special presentation by Rick on May 8th. The event will be free and open to the public, but registration will be required. Guests can register by calling 877-813-3329 x 412 or by emailing Jeremy.collins@nationalww2museum.org.

If you would like to pre-order the book from Museum, whether you are able to attend the May 8th event or not, please contact the Museum store at 877-813-3329 x 285 or email at museumstore@nationalww2museum.org.