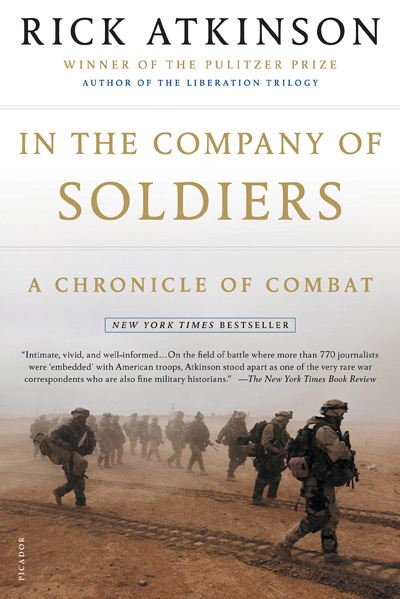

Excerpt from In the Company of Soldiers

You can download Chapter 1 of the book as a PDF file, or read below:

Chapter 1: ROUGH MEN STAND READY

The road to Baghdad began in the Shoney’s restaurant parking lot at the Hopkinsville, Kentucky, mall at 8 A.M. on Wednesday, February 26, 2003. Snowflakes the size of chicken feathers tumbled from the low clouds. How to Lose a Guy in Ten Days and The Recruit took top billing on the marquee of the Martin Five Theaters. Sixty journalists, their hair whitened and wet with snow, straggled onto two buses chartered by the Army to haul us to nearby Fort Campbell, home of the 101st Airborne Division. “I just spilled my fuckin’ coffee,” a reporter announced to general indifference. A young woman holding a small mirror limned her eyes with mascara; her hand trembled slightly. An impatient Army officer called roll from a clipboard, then nodded to the civilian driver, who zipped up his Tennessee Titans windbreaker and shut the door. “Let’s go,” the officer told the driver. “Man, this is like herding cats.”

As the bus eased through a military police checkpoint at the back gate, I scanned a seven-page document sent by e-mail two days earlier. “This is a formal invitation for you to embed with elements of the 101st Airborne during our deployment,” it began. “The agenda calls for travel via military contract transportation from Fort Campbell to the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) Area of Responsibility.” Some 777 reporters and photographers were to join various Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps units under a Defense Department plan for covering a war with Iraq that now seemed inevitable and imminent. A twelfth of those journalists would be sprinkled throughout the 101st Airborne, in various battalions, brigades, and support units.

The document included rules and suggestions. For “messing and billeting purposes,” reporters were “considered the rank of ‘major’ equivalents,” a putative commission that overpromoted most of us by at least four grades. Reporters could not carry weapons and should not bring “colorful news jackets.” A dozen recommended inoculations included anthrax, smallpox, and yellow fever. Each journalist was to bring a sleeping bag, “two months’ worth of personal hygiene items,” dog tags—“helicopter crashes tend to mess up the bodies,” an officer had told me with a wink— and fieldcraft articles ranging from a pocket knife and flashlight to goggles and baby wipes. “Items to avoid” included curling irons, hair dryers, pornography, and alcohol.

“The current conditions in the area of operations are being described as ‘austere.’ You should not anticipate having laundry facilities available. Hand washing in a bucket is the norm. The Army will provide you with MREs (Meals Ready to Eat). We look forward to working with you on our next Rendezvous With Destiny!”

The snow tapered off as the small convoy rolled across Fort Campbell. A billboard declared: “Screaming Eagle Country. Salute With Pride.” The 105,000-acre post straddles the Kentucky-Tennessee border and is populous enough to require multiple zip codes. Many wood-frame World War II buildings remain in use, such as the division headquarters. An electronic sign near a traffic intersection flashed advertisements, including notices for “Bingo Bingo Bingo Bingo World” and “Air Assault Towing and Storage.” A new black stone memorial across the street commemorated the division’s classic battles and featured an engraved quotation from Major General William C. Lee, a World War II commander who is considered the founding father of U.S. Army airborne operations: “We shall habitually go into action when the need is immediate and extreme.”

Waiting outside a small Army conference center was Major Hugh Cate III, the division public-affairs officer, whom I had already met during a reporting trip to Fort Campbell in early January. An affable former West Point rugby player from Alabama, Cate—known to his friends and family as Trey—shook hands and squeezed elbows as the reporters trooped from the buses. Pulling me aside, he asked, “You ready to go? We have forty-nine aircraft leaving in the next seventy-two hours. General Petraeus and most of the command staff are already in Kuwait. You and I are leaving tomorrow night.”

Inside, a large U-shaped table dominated the room. Immense historical photographs covered the walls, depicting the division in France, Holland, Vietnam, and, during the 1991 Persian Gulf War, southern Iraq. One photo famously captured General Dwight D. Eisenhower in earnest conversation on the eve of D-Day with young paratroopers about to board their aircraft for the jump into Normandy. Created in August 1942, the 101st Airborne had been featured in the Stephen Ambrose best-seller Band of Brothers, which subsequently became a popular ten-part television series.

Cate got everyone seated, then dimmed the lights and cued a five-minute indoctrination video. While an unseen chorus sang a treacly anthem—“When we were needed / We were there”— images flashed by of Bastogne, Tet, and Desert Storm, and of coffins from Gander, Newfoundland, where a battalion returning from peacekeeping duty in the Sinai peninsula had been obliterated in a plane crash in December 1985. A wall poster on the second floor of the conference center quoted George Orwell: “People sleep peaceably in their beds at night only because rough men stand ready to do violence on their behalf.”

Not since 1974 had the 101st Airborne been a parachute unit, which made the nomenclature inconvenient if not annoying. Rather, the division had been converted into an “air assault” force, exploiting the “vertical envelopment” tactics first tried by U.S. Marines in the Korean War. Equipped with 256 helicopters, the 101st could mount deep attacks behind enemy lines with six dozen Apache gunships—far more than any of the Army’s nine other divisions—while simultaneously shuttling up to four thousand soldiers at least a hundred miles in six hours with Blackhawk and Chinook transport helicopters. “Powerful, Flexible, Agile, Lethal,” a division briefing paper asserted. “Trained and ready to fight and win.” Collectively and formally, the seventeen thousand soldiers were now the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault). Informally, and with considerable pride, they called themselves the Screaming Eagles, and greeted one another with the snappy salutation “Air assault!”

All this became clear over the next few hours in a series of briefings. A grizzled civilian public-affairs officer named George Heath leaned over the podium and said, “If you prefer vegetable MREs to regular MREs, if you have a particular brand of cappuccino you prefer, if you’d rather have a room with a morning view rather than an evening view, just let us know and we’ll see if we can accommodate you.” Momentary confusion rippled through the journalists, a blend of hope and skepticism, until Heath’s flinty squint revealed his facetiousness.

The Fort Campbell hospital commander displayed slides of four horribly disfigured smallpox victims, their faces blistered beyond even a mother’s love. An autopsy slide of a Russian victim of inhalation anthrax showed a human brain transformed by the bacteria into a black, greasy lump. “A sequence of three vaccination shots has proved 92.5 percent effective in protecting rhesus monkeys from anthrax,” the commander said. “In rabbits, it’s 97 percent.” Journalists who wanted smallpox or anthrax immunizations filled out several government forms— joking nervously about whether to check “monkey” or “rabbit”—and then marched to a nearby clinic where Army doctors waited to prick them.

Those who still had an appetite were bused to the Fort Campbell food court for lunch at Anthony’s Pizza or Frank’s Franks. Vendors in the atrium peddled T-shirts demanding “No slack for Iraq!” as well as 101st Airborne Division baseball caps and cheap lithographs of raptors in various spread-eagle attitudes.

Back at the conference center, the briefings continued all afternoon. A sergeant with expertise in nuclear, biological, and chemical matters, known simply as NBC, demonstrated how to don an M-40 protective mask. “Most of the Iranians who died from chemical weapons in the Iran-Iraq war were wearing beards, and their pro masks didn’t seal properly,” the sergeant said. “If you have a beard, I recommend you lose it.”

Among those most discomfited by this advice was Jim Dwyer, a wry, gifted reporter for The New York Times who would become my closest comrade for the next seven weeks. The son of Irish immigrants and winner of a Pulitzer Prize in 1995 for his lyrical columns about New York City, Dwyer was an eleventh-hour draftee into the ranks of Times war correspondents. “If you’re having a midlife crisis,” his doctor had asked him before the deployment, “why don’t you get a girlfriend like other men your age?” At forty-six, he was the proud owner of a thirteen-year-old beard. Dwyer asked the NBC sergeant several questions of a rear-guard sort, then surrendered. The next morning he would appear with his plump, clean-shaven Irish face aflame with razor burn but ready for masking.

As masks were issued, reporters debated the probability that Saddam Hussein would attack with sarin gas, botulinum toxin, or mustard gas. Like most reporter conclaves, this discussion was long on opinion and short on hard intelligence; a narrow majority held that “getting slimed,” as the Army called a chemical attack, was probable.

“The signal for a gas attack is three honks of a horn or someone yelling, ‘Gas! Gas! Gas!’ ” the sergeant continued. “How do you know when there’s a gas attack? When you see someone else putting on their mask.” I thought of Wilfred Owen and his poem “Dulce et Decorum Est”: “Gas! Gas! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling.” The standard for donning the mask was nine seconds. I was not sure I could even extract it from the case in nine seconds, much less get it seated and strapped on.

Next the sergeant produced a canvas bag containing the Joint Service Lightweight Integrated Suit Technology, a cumbersome name for a cumbersome garment more commonly known as a JLIST, pronounced “jay-list,” and made of charcoal-impregnated polyurethane foam. “The standard for going from MOPP zero— that’s Mission-Oriented Protective Posture—where you only have your mask in the case, to MOPP four, which includes putting on the full suit, vinyl boots, mask, and gloves, is eight minutes.” Piece by piece the sergeant pulled on his gear, periodically advising us to secure this or that with “the hook-andpile fastener tape.” It took several references before I realized that he was talking about Velcro. The expert needed more than eight minutes to get outfitted and accessorized. When he peeled off the mask after just thirty seconds, he was sweating like a dray horse.

“It’s been pretty lighthearted so far,” said Major Cate, moving to the podium. “But I just want you to know that this is serious stuff.” Anthrax, smallpox, sarin, botulinum, mustard: in truth, the day had not seemed excessively frivolous. Cate reviewed some of the ground rules for covering combat operations. No journalist could be excluded from the front line because of gender; if a female reporter wanted to live with a rifle company, so be it, even though by law female soldiers could not serve in such units. “Our attitude is that information should be released and that there should be a good reason for not releasing it rather than that it should be suppressed until someone finds a good reason for letting it out,” Cate added. This statement provoked mild skepticism, both as a statement of policy and as a syntactical construct.

Safety was paramount, he continued. “Dead press is bad press.” Not a soul in the room disagreed. “There’s gonna be bad news. There’s gonna be tension between people. Take a big bite of that patience cheeseburger.”

A civil affairs expert then delivered the same lecture on Iraqi culture that thousands of soldiers were hearing. “Never use the A-okay or thumbs-up hand gestures,” he advised. “They are obscene in the Arab culture. I believe the A-okay sign, with thumb and forefinger, has to do with camel procreation.” (I would recall this assertion a month later when thousands of jubilant, liberated Iraqis flashed thumbs-up at passing American soldiers.) Another expert gave a twenty-minute summary of Iraqi history and geography. Three quarters of Iraq’s 24 million people lived in cities. Twelve percent of the country was arable. Baghdad’s population exceeded 5.5 million. The average high temperature in Baghdad in May topped 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The oil-for-food program, organized under United Nations’ sanctions, allowed Saddam to export about 75 percent as much oil as he had sold before the 1991 war; smuggling earned him another $3 billion annually. The briefing ended with another cultural warning: “Never point, or show the bottoms of your feet, to Arabs.”

The final lecture in a long day came from Captain Nick Lancaster, who identified himself as the division’s chief of justice. Wars had rules, Captain Lancaster began. Internationally recognized combat regulations were “intended to prevent suffering for the sake of suffering. Basically we want to be the good guys. We want everybody to know that we are the good guys and that we play by the rules.” A rule of thumb for combatants held that “suffering must not be excessive. There is a Department of Defense lawyer in Washington whose job is to review all weapons under consideration for purchase to determine if they comply with the laws of war and will not inflict unnecessary suffering.” Once a soldier was wounded, he could no longer be considered a combatant. Lancaster acknowledged that the rules

of war had many finely parsed legal distinctions. A parachutist, for example, is a pilot descending by chute; a paratrooper—a different species altogether, in the eyes of the law—is a combatant deliberately attacking by airborne means.

He raced through other legal nuances. The basic rule for treating captured Iraqis would be “humane treatment, which means food, water, medical treatment. If they are formally given the status of EPWs—enemy prisoners of war—they get other rights, including access to tobacco and musical instruments.”

Finally, the captain warned, General Order No. 1 would be enforced during the deployment. Usually known as the “no alcohol” edict, the order in fact contained numerous clauses, some of which Lancaster said had been violated the previous year in Afghanistan by soldiers from the 3rd Brigade of the 101st. Among the prohibitions: No privately owned weapons in a combat zone. No entry into religious sites for reasons other than military necessity. “We don’t want to assault their sensibilities by having a bunch of soldiers trooping through a mosque,” Lancaster explained. No religious proselytizing. No looting of archaeological sites. No black marketeering. No pets.

A reporter asked whether General Order No. 1 applied to embedded journalists. Lancaster paused judiciously. Prosecutions were unlikely, he admitted, then added, “My advice would be that you comply.”

Any U.S. military campaign in Iraq would seek to minimize damage to the country, the captain concluded. The reason, however, was less an issue of jurisprudence than of enlightened selfinterest. “The more infrastructure that’s still there after the war, the less that we will have to rebuild,” he said. “And the quicker we can leave.”

As we filed from the conference room for a final night in our Clarksville hotels, it occurred to me that Captain Lancaster had articulated what American soldiers have fought for in every conflict since the Mexican War: the right to go home quickly.

We were on our way—slowly, the Army way.

By late afternoon on Thursday, February 27, in a journalistic diaspora, the reporters had been farmed out to their assigned units. The 101st comprised seven brigades, each commanded by a colonel who was like a duke in the larger kingdom. Each of the three infantry brigades, for example, had roughly 3,500 soldiers and typically was expanded into a “combat team” with its three infantry battalions augmented by an artillery battalion, a couple of aviation battalions, and company-sized units of engineers, communications experts, intelligence analysts, and air defense troops. Most of the division’s equipment, from helicopters to howitzers, had already been shipped by rail to Jacksonville, Florida, and was now aboard five huge ships steaming to Kuwait. The soldiers, however, would fly on chartered airliners, carrying their personal baggage, individual weapons, gas masks, night-vision goggles, and the harness of buckles and shoulder straps known as an LBE, for load-bearing equipment.

I was assigned to division headquarters, where I was the only reporter shadowing the commander, Dave Petraeus. I had known Petraeus casually since he was a major working for the Army chief of staff in the early 1990s. My premise in requesting this assignment was that a division command post in combat afforded a good vantage point for looking down, into the operations of its subordinate brigades and battalions, as well as for looking up, into corps operations. I also knew that Petraeus was a compelling figure: smart, articulate, and driven. “Probably the most talented person I have ever met in the Army,” General Barry R. McCaffrey, a retired four-star, had recently said of Petraeus. “This guy has sparks jumping off of him.”

As the son of an infantry officer, I had been around the Army all my life, including extended stints as a correspondent in Somalia, Bosnia, and the Persian Gulf in 1990–1991. I had also written books about the Army in Vietnam, in the Gulf War, and, most recently, in North Africa during World War II; for four years I had been on extended leave from the Post, and I was engrossed in researching a narrative history of the campaigns in Sicily and Italy in 1943–1944 when the newspaper solicited my temporary return to journalism. This view of the Army, I believed, would be uniquely intimate.

That it would be a view of an army at war seemed probable. A confrontation over Iraqi disarmament had persisted between Washington and Baghdad virtually since the end of the Gulf War in March 1991. Iraq without doubt had violated various United Nations Security Council resolutions; renewed American resolve had goaded the Security Council, in November 2002, to unanimously approve a tougher resolution demanding the return of UN weapons inspectors to Iraq after a four-year absence, and the inspectors’ unrestricted access to facilities throughout the country. Grudging, obnoxious, and ever recalcitrant, Saddam Hussein nevertheless over the winter readmitted the inspectors, and he destroyed dozens of missiles deemed in violation of UN range limitations.

Yet President George W. Bush and his senior advisers insisted that Iraq prove that it had dismantled programs to make nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. “You do know they have weapons of mass destruction, don’t you?” Paul Wolfowitz, the deputy defense secretary, told the chief UN weapons inspector. Bush also asserted that “confronting the threat posed by Iraq is crucial to winning the war on terror,” although he presented no evidence linking Baghdad to the Al-Qaeda killers responsible for the atrocities of September 11, 2001.

The administration’s cocksure bellicosity alienated many allies, particularly in light of Bush’s repudiation of various international agreements—from the Kyoto Protocol on the environment, to the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, to the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty—as well as a new U.S. national security doctrine, published in September 2002, that endorsed preemptive attacks against perceived threats. Millions of antiwar demonstrators had marched in 350 cities around the world on February 15. Another resolution, authorizing force against Iraq and introduced at the Security Council the day before my arrival in Kentucky, had little hope of attracting even a simple majority. Opinion surveys showed that a thin majority of Americans supported military action against Iraq, even without explicit UN appoval. “At some point,” Bush declared, “we may be the only ones left. That’s okay with me. We are America.” If the dispatch of U.S. forces to Southwest Asia, which had begun in earnest the previous summer, initially helped stiffen international resolve toward Iraq, now the floodtide of troops appeared to be driving the United States inexorably toward war. The 101st Airborne Division’s was the most conspicuous deployment to date, an unambiguous and perhaps irreversible signal of deadly intent.

The Personnel Marshaling Area at Fort Campbell was a dim, drafty warehouse with a concrete floor. Two hundred and ninety-four passengers, designated collectively as Chalk 19, included staff officers, the division band, the 101st headquarters company, a signal unit, MPs, Trey Cate’s public-affairs warriors, Jim Dwyer of the Times, who was assigned to the division’s assault command post, and me. The soldiers wore desert camouflage uniforms and suede desert boots. Smokers huddled outside on a loading dock. A voice carried above the hubbub: “Hey, DeSouza. Just because you’re smoking a fucking cigarette is no reason somebody else should hold your fucking weapon.” Another voice sang out, “I need a hug. I need a hug.”

At 4 P.M., after two hours of general milling, we hauled our bags into a parking lot, where “Chalk 19” was scrawled on a pair of immense twenty-four-wheel flatbed trucks. In a lifetime of travel I have never learned to pack concisely, and my High Sierra rucksack—Chinese red in a sea of Army green—bulged with reporter notepads, clothing for hot weather, clothing for cold weather, extra batteries (sizes AA, AAA, and C), extra computer and satellite-phone cables, a sleeping bag and foam mat, a power strip, two flashlights with red lenses, a Gerber folding knife with enough attachments to build a house or perform a heart-lung transplant, a tape recorder, spare tapes, extra reading glasses, a flak vest, a helmet, a shaving kit with two months’ worth of toiletries, and too many books I had never read and would never read. With a heavy grunt I managed to heave the thing onto the flatbed, certain and perhaps a bit glad that I would never see it again.

In two shoulder bags I still had the gas mask and JLIST, a laptop, two satellite phones, a digital camera, a thick sheaf of unintelligible instructions on how to operate these things, pens, pencils, more notebooks, another flashlight, and various items I could only think of collectively as stuff. Whatever happened, I wondered, to the doughty war correpondent with a pencil, a pad, and a battered Underwood? A modern hack’s greatest fear, besides running out of gin, was having no means to write or to transmit written copy to the home office; for the sake of redundancy, given the harsh conditions that awaited us, within two weeks I was to accumulate three satellite phones; three digital cameras; a loopy assortment of cables, cords, wires, and adapters; and two laptops, including one variant encased in a metal box that supposedly could withstand being run over by a Humvee. There was irony here: I have never been comfortable in a world fraught with electrons. A week earlier, upon arriving for laptop and satellite-phone instruction at The Washington Post, I overheard one technician tell another, “The guy coming in this morning is a real technology moron.” I could only concur.

From the parking lot we were herded to another holding tank in a large cafeteria. A television near the front door was tuned to CNN; the crawl across the bottom of the screen noted that the national threat level had been lowered from orange to yellow. “Pass the word,” a soldier in front said. “No weapons or LBEs on the new furniture in the mess hall. Pass it on.” Inside, a soldier reading the Odyssey laid his head on a table and dozed off, no doubt dreaming of lotus-eaters and men turned to swine.

At 5:45 P.M. we were rousted and sent back outside. Fog and dusk had settled over Fort Campbell. “Let’s go, let’s go. Chalk nineteen over here,” called Sergeant First Class Henry DeGrace, a senior noncommissioned officer for the headquarters company. “Give me a formation. Troop, Ten-hut! Who does not have a mask?” Silence. “Who is missing their protective mask?” Silence. DeGrace held up a canvas sack and read the stenciled number. “Mask 104.” A miscreant private skulked forward to claim it.

A squadron of buses pulled up. DeGrace stood in the door of the first bus and looked each boarding soldier in the eye. “Got all your sensitive items?” “Yes, sergeant,” they answered. “Yes, sergeant.” The driver, a civilian with brilliantined hair and thick glasses who referred to his vehicle as Big Boy, stood to the side. “There’s fifty-five seats, if that helps,” he said as the NCOs repeatedly counted noses. “You need to lose them soft caps,” DeGrace barked. “Only Kevlars from here on.” He pronounced the term as a single word: softcaps. With a hiss of air brakes the convoy rolled toward the airfield, led by a police cruiser with flashing blue lights. “I feel important,” DeGrace said, with just the right sardonic pitch.

I noticed a 10th Mountain Division combat patch on his right sleeve and asked DeGrace if he had been in Somalia when the unit deployed to Mogadishu in the mid-1990s. He had indeed, and he had also served in Haiti, in Bosnia, and on various other deployments. “I’ve been married seventeen years and my wife has been through every one of them.” He removed his helmet and showed me a yellowing snapshot, tucked in the webbing, of his four children. “The oldest one turned sixteen this month,” he said. “This is the same photo of them I had in Somalia, and I kept it in the same place. I told my kids we’ll be home when the job is done. I hope this is the last time I have to do this.”

DeGrace was lean and quick-spoken, with a handsome hussar’s mustache. A native of New Bedford, Massachusetts, he’d joined the Army in 1985. He told me that his father, also named Henry, had enlisted at sixteen, deceiving the authorities with the birth certificate of an older brother who had died in infancy. Eventually promoted to sergeant, Henry Senior had surrendered three stripes in order to join the newly created 101st Airborne Division, and had fought with G Company of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment from Operation MARKET GARDEN, in Holland, until the end of the war. Henry Senior was eighty-two years old and had worked in the post office for forty-five years after the war; Henry Junior had a Screaming Eagle tattooed on his calf. It was that kind of unit, a confederacy not only of foxhole brothers but also of fathers and sons.

The buses pulled up to an empty hangar and Chalk 19 trooped inside. Metal bleachers lined two walls and the troops settled in with a clatter of rifles. A chaplain at a table draped with a desert camouflage dropcloth handed out vest-pocket New Testaments and a devotional volume titled The Power of Crying Out. “It’s really good,” he told me pleasantly. “Would you like one?” I turned to the first page, and a verse from Psalm 86: “In the day of my trouble I will call upon You, for You will answer me.” Various chapters included advice on “release from demons” and “self-control.”

The atmosphere in the hangar was neither jovial nor somber. For most troops, the day of trouble was not here yet, only the day of leaving. Soldiers who still required inoculations peeled off their uniform blouses and lined up to be pricked against smallpox or hepatitis or influenza. Sergeants circulated through the hangar, herding female soldiers toward a restroom for a final pregnancy test; expectant mothers could not deploy to a combat zone. A young specialist groaned and tossed her rucksack on the floor. “Watch my shit, will you?” she asked a male corporal before joining the long line.

Snatches of conversation drifted from the bleachers. A few soldiers made final, teary calls on their cell phones. Some Chinook helicopter pilots, I knew, had been home from Afghanistan for only three weeks before shipping out for Kuwait. “I wonder if I’ll ever get one consecutive year at home,” a sergeant first class told another soldier. “This is my fourth year in a row to deploy. I’d like to spend just one year at home. Maybe when I retire.” He sounded more weary than angry. “I took a job in the headquarters company because I didn’t think we’d go anywhere unless the whole division went. So guess what? The whole division is going.”

Much palaver was devoted to whether Chalk 19 would land in Kuwait City before midnight on February 28, which would earn each soldier an income tax exemption for the entire month of February. Few soldiers considered themselves mercenaries, but most were keenly aware of the deployment pay entitlements. “Desert Dollars,” as the Fort Campbell newspaper called the benefits, included a $3.50 per diem, $100 per month in separation pay, $150 per month in hostile-fire pay, a $241-per-month basic subsistence allowance, and up to $5,533 in monthly salary taxfree under the “combat zone exclusion.” A sergeant with two young children told me he was already borrowing against the extra income; at Fort Campbell, he was so strapped for cash by the end of each month that he rarely ate lunch. “It’s an extra six or seven hundred bucks a month I can really use,” he said.

There was a commotion in the middle of the hangar and I spied an officer I had known since the Gulf War, when he was a major. Now Benjamin C. Freakley was a brigadier general and the assistant division commander for operations, often referred to simply as the O. Freakley was a force of nature, an oldfashioned warfighter with a big heart and five sons. Another West Point rugby player, he was a devout Methodist, a collector of antiques, a natural pedagogue, and a talented drummer whose solo rendition of “Wipeout” at the division Christmas party was still much discussed. Freakley had been delegated by Petraeus to oversee the deployment; he was unhappy both at being left behind for two weeks and at various bureaucratic malfeasances, which he was now trying to correct.

He halted his finger-jabbing long enough to let me introduce him to Dwyer, who would eventually join the assault command post, typically the O’s domain in combat. “The plan is changing quickly,” Freakley told us. The Turkish government appeared disinclined to let the 4th Infantry Division attack through eastern Turkey into northern Iraq. “If the planners want to protect the oil fields in the north, the 101st would be a good candidate for that job.” Asked how long he anticipated the campaign would last, he mulled the question for a moment. “Two weeks if it goes well, two months if it doesn’t. If it gets into Baghdad, or the other cities, the plan is to use precision strikes by identifying points of resistance and hitting quick and hard, then getting out. There will be no kicking-in of doors.”

Freakley strode off to resume his scourging. At 10 P.M., Chalk 19 was ordered outside yet again, this time to a small hangar on the edge of the runway. Each soldier carried twenty rounds of ammunition in the unlikely event the 101st would have to come off the plane shooting. I pulled my wheeled backpack behind me, feeling like a tourist. An assistant chaplain, Major Len Kircher, ruminated on the flurry of marriages that had preceded the deployment. One accommodating local magistrate had even been dubbed the Love Judge. Kircher disapproved. “I don’t do spur-of-the-moment jobs,” he said. “I won’t marry teenagers and I won’t marry privates. The failure rate is too high.”

Several hundred heavily armed soldiers listened impassively as an MP read a required government warning: “It is a federal crime,” she said with no trace of irony, “to carry concealed weapons aboard an aircraft.” Then, as directed, the troops shouldered their rifles and grenade launchers and shambled onto the runway.

Four big charter jets waited in the fog, including a Northwest Airlines Boeing 747 and an airliner whose fuselage advertised Hawaiian vacations. The runway lights were orange and weird,casting long shadows. Chalk 19 tramped in a column along the tarmac to World Airways Flight 6208. As the soldiers climbed the boarding ramp and stowed their weapons beneath the seats, butts toward the aisles, a flight attendant apologized over the public-address system: because of a broken valve, the aircraft had no running water. Each passenger was handed a liter of bottled water, “for flushing.”

At 12:30 A.M. on Friday, February 28, the plane lifted into the night. Spiderman leaped around the cabin during the in-flight movie. At 3 P.M. German time, we descended over the golden Hessian landscape to refuel in Frankfurt. Three-bladed windmills slowly turned in the afternoon sun. Old Europe looked tranquil, far from war and rumors of war, and ready for happy hour to begin the Wochenende. The plane taxied past the Luftbrücke memorial, commemorating the Berlin airlift organized by the U.S. Army in 1947. The ironies, I thought, were beginning to pile up. For an hour, soldiers wandered through a gift shop, studying the Hummel figurines and beer steins and T-shirts boasting, “I Drove the Autobahn.”

The second leg began with a flight steward reminding passengers that “this is a nonsmoking flight, and that includes smokeless tobacco.” Soldiers dutifully put away their tins of Copenhagen. Across the Alps and down the boot of Italy we flew through the night. Below the glitter of Naples, I picked out the dark curve of Salerno, where so many boys had died sixty years before. Most of Chalk 19 was watching Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. A soldier across the aisle was engrossed in Field Manual 3-19-4, “Military Police Officer Leader’s Handbook.” If we seemed more like a tour group flying off on holiday than an army marching to war, the very familiarity of our conveyance seemed to accent the anxious sense of uncertainty.

Across the Mediterranean, the plane flew up the Nile, then banked east at the Valley of the Kings to cross the Red Sea and Saudi Arabia. As we descended on the final approach, the pilot ordered all window shades lowered and cabin lights extinguished to make the plane less conspicuous to anyone below armed with a shoulder-fired missile and bad intent. “We really do appreciate everything you are doing for us and our nation,” a flight attendant added. “Godspeed.”

Seventeen hours after leaving Fort Campbell, the plane touched down in Kuwait City at 1:50 A.M. local time on Saturday, March 1, too late to qualify for a tax-exempt February. The first three soldiers down the ramp were eighteen, nineteen, and twenty-three years old. They did not mention the money.

Copyright © 2004 by Rick Atkinson. All rights reserved.