Major Figures from The Liberation Trilogy

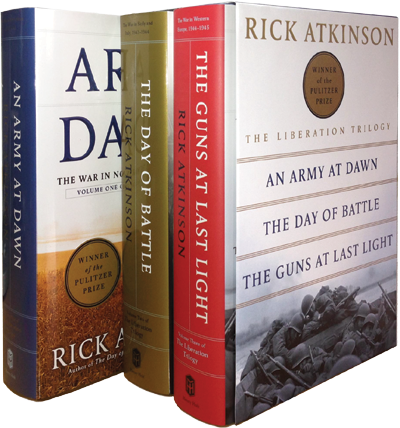

An Army At Dawn

Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Commander, Operation TORCH. Despite never having commanded even a platoon in combat, Eisenhower found himself leading perhaps the boldest military expedition ever launched by the United States. His inexperience plagued him for months in North Africa, both as a battle leader and as the head of a fractious international coalition; even before the debacle at Kasserine Pass in February 1943, he feared that he was about to be relieved and sent home. The campaign in North Africa would test Eisenhower’s abilities as a leader, much as it would test American aspirations to be a world power.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

Commander, Panzer Army Africa. “Rommel, Rommel, Rommel!” Prime Minister Churchill had exclaimed. “What else matters but beating him?” Like most of history’s conspicuously successful commanders, he had an uncanny ability to dominate the minds of his adversaries. The son and grandson of schoolteachers from southwest Germany, he had rocketed from lieutenant Colonel to field marshal in four years. His successes in Africa showed the audacity, tactical brilliance, and personal style that won him the sobriquet of Desert Fox; but Africa would also reveal the limitations of his generalship and his influence on his political master, Adolf Hitler.

Major General George S. Patton, Jr.

Major General George S. Patton, Jr.

Commander, Task Force 34 and U.S. II Corps. As the charismatic commander of the American force that invaded Morocco during Operation TORCH, Patton quickly became a national hero in demonstrating his most conspicuous attributes: energy, will, a capacity to see the enemy’s perspective, and bloodlust. Further combat in Tunisia would burnish his reputation while revealing his defects: a disregard of logistics; a penchant for bullying subordinates; and an archaic tendency to assess his own generalship on the basis of personal courage under fire. “On reflection, who is as good as I am?” he asked his diary. “I know of no one.” He was, a British officer concluded, “smart, blasphemous, fit, and glamorous…but born in the wrong century.”

Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen

Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen

Commander, U.S. 1st Infantry Division. Even his name swaggered, an admirer once wrote. Allen surely embodied the unofficial motto of his unit, the Big Red One: “Work hard and drink much, for somewhere they’re dreamin’ up a battle for the First.” If he was “the fightingest man I ever met,” as one aide averred, Allen also was innovative, tactically gifted, and devoted to both his men and to God. His penchant for provoking superiors would cause trouble, in Tunisia and again in Sicily. “The most difficult man with whom I have ever had to work,” Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley said of him, “fiercely antagonistic to any echelon above that of division.”

The Day Of Battle

Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark

Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark

The senior U.S. military commander in Italy. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was Clark’s patron and boss, considered him “the best organizer, planner and trainer of troops that I have met. In preparing the minute details…he has no equal in our Army.” Long-limbed and angular, Clark had dark eyes that constantly swept the terrain before him; to a British general, he evoked “a film star who excels in Westerns.” Yet he could also be short-tempered, aloof, and a compulsive self-promoter. No one played a larger role in the battles for Salerno, Anzio, the Rapido River, and Rome: more than sixty years after World War II, few figures remain more controversial.

Major General Lucian K. Truscott, Jr.

Major General Lucian K. Truscott, Jr.

Commander of the 3rd Infantry Division in Sicily and Italy; then the senior Allied commander at Anzio. Before enlisting in the cavalry during World War I, Truscott taught in rural Oklahoma for six years. The schoolmaster never left him—“You use the passive voice too damn much,” he once chided a subordinate—and he wrote long, searching critiques of subordinate performances (as well as long, loving letters to his wife, Sarah.) Even in combat he cherished cut flowers on his desk and ontological inquiries: a staff meeting might begin with Truscott asking the division chaplain, “What is sin?” Many considered him the finest field commander in the U.S. Army.

Major General Geoffrey Keyes

Major General Geoffrey Keyes

Deputy to George S. Patton in Sicily; then commander of the U.S. II Corps from Salerno through the capture of Rome. As a West Point football star, Keyes was said to be “the only man who could stop Jim Thorpe” on the gridiron. During the Sicilian campaign, one officer wrote, “the impetuous, vitriolic, histrionic Patton is considerably leavened by the calm, deliberate, circumspect Keyes.” A devout Roman Catholic who attended mass each morning, Keyes was an exceptional tactician who confided his wry and often trenchant reflections to a diary, revealed publicly for the first time in The Day of Battle.

Lieutenant Colonel John J. Toffey, III

Lieutenant Colonel John J. Toffey, III

A battalion and deputy regimental commander from Sicily to Rome. Son of a general, grandson of a Congressional Medal of Honor winner, Jack Toffey had commanded American troops since the first landings in North Africa. Both battle-wise and battle-weary, he was emblematic of those officers who had learned much through hard combat and whose influence on a hundred European battlefields would be both decisive and disproportionate to their numbers in the U.S. Army. “War is as Sherman says,” he wrote his wife, Helen, “and has no similarity with cinema or storybook versions.”

The Guns at Last Light

General Dwight D. Eisenhower

General Dwight D. Eisenhower

The supreme commander, Allied Expeditionary Force. For years, Eisenhower had pondered how to liberate Europe—as a War Department planner, as the senior American soldier in London in 1942, and then as the architect of invasions in North Africa, Sicily, and mainland Italy. President Roosevelt considered him “the best politician among the military men. He is a natural leader who can convince other men to follow him.” Nearly all subordinates agreed that he was charismatic and profoundly fair, but some questioned his skills as a field commander. “When it comes to war,” complained General Bernard Montgomery, “Ike doesn’t know the difference between Christmas and Easter.”

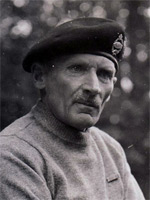

General Bernard L. Montgomery

General Bernard L. Montgomery

Commander of Allied ground forces in Normandy. Wiry and elfin, with a narrow vulpine face, Montgomery by D-day was the most famous general in the British empire, “as sharpened and as ready for combat as a pointed flint,” in one admirer’s phrase. Energetic, meticulous, and supremely confident, he could also be bumptious, self-absorbed, and insulting to his comrades, particularly the Americans. Montgomery was “Master” to his aides, “this Cromwellian figure” to Winston Churchill, “God Almonty” to the Canadians, and “the little monkey” to General George S. Patton. Eisenhower came to believe that “Monty is a good man to serve under, a difficult man to serve with, and an impossible man to serve over.”

Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.

Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.

Assistant commander of the 4th Infantry Division. Short, gnarled, and bandy-legged, son of the twenty-sixth president, Roosevelt had been shot, gassed, and decorated in World War I before resuming a civilian career that included stints as assistant secretary of the Navy, chairman of American Express, governor-general of the Philippines, and governor of Puerto Rico. Returning to uniform in World War II, he fought heroically in Tunisia but was relieved of command in Sicily. Given another chance, he would be the most senior officer to land on Utah Beach in the first waves on June 6, 1944, a man both valiant and doomed. “We’ve known joy and sorrow, triumph and disaster,” he wrote his wife before D-day, “all that goes to fill the pattern of human existence.”

Lieutenant Colonel John Knight Waters

Lieutenant Colonel John Knight Waters

Prisoner of War #4161. Captured in Tunisia in February 1943, Waters—the son-in-law of General Patton—eventually was interned with other American officers, first in Poland, and then, after a forced march across Germany in mid-winter, at Oflag XIII-B, a camp in the Bavarian town of Hammelburg. Waters kept not only a “Wartime Log,” in which he tracked daily prison rations to the gram and even saved food labels from relief-package cans, but also a detailed personal journal. The Guns at Last Light discloses for the first time his notes on the ill-fated raid launched by Patton in March 1945 to free inmates at Hammelburg. “Shot while under white flag by German,” Waters wrote. “Operation & hospital. Suffering.”