“THE GREATEST FIREPOWER EVER ASSEMBLED ON THE FACE OF THE EARTH”

Air Support for OVERLORD

by Joseph Balkoski

Posted March 3, 2014

Ike Eisenhower had to admit that his best friend “Gee” Gerow’s soldierly skills surpassed his own. Those talents would be needed, the supreme commander presumed, when Major General Gerow’s command surged ashore on Omaha Beach on D-Day. However, just thirty-eight days before the invasion—on April 28, 1944—a concerned Ike noticed that the strain of command had deeply affected Gerow. That afternoon, on a railroad siding near Taunton, England, Eisenhower and Gerow sat in Ike’s Pullman coach, code-named BAYONET, to hash out solutions to the intractable challenges of amphibious warfare. “Gerow seemed a bit pessimistic,” a witness wrote, “and finally Ike said to him that he should be optimistic and cheerful because he has behind him the greatest firepower ever assembled on the face of the earth.”

Ike had a point. When one totaled the bomb tonnage of the warplanes based in Britain and contemplated the impact of that immense destructive power on the enemy, surely the Germans’ ability to resist the invasion would be crippled. But as the frustrated supreme commander would soon learn, the Anglo-American high command’s divergent views on strategic air power generated acrimonious disputes that came close to nullifying the “firepower” boast Ike had made to Gerow. True, even the most enthusiastic proponents of strategic air power, such as the U.S. Army Air Force’s Lt. Gen. Carl Spaatz and the RAF’s Air Chief Marshal Arthur “Bomber” Harris, agreed that heavy bombers must contribute in some way to OVERLORD. Squabbles over the nature of that contribution, however, nearly ripped the Allied high command apart. Who would command strategic air in OVERLORD? How long would that command arrangement last? What missions would the heavy bombers be expected to carry out?

General Carl Spaatz (at left) and Lt. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle (center) at a debriefing of an Eighth Air Force bomber crew in March 1945. Prior to D-Day, an Army Air Force officer recalled that Spaatz once dismissed OVERLORD by noting, “This [expletive] invasion can’t succeed, and I don’t want any part of the blame.”

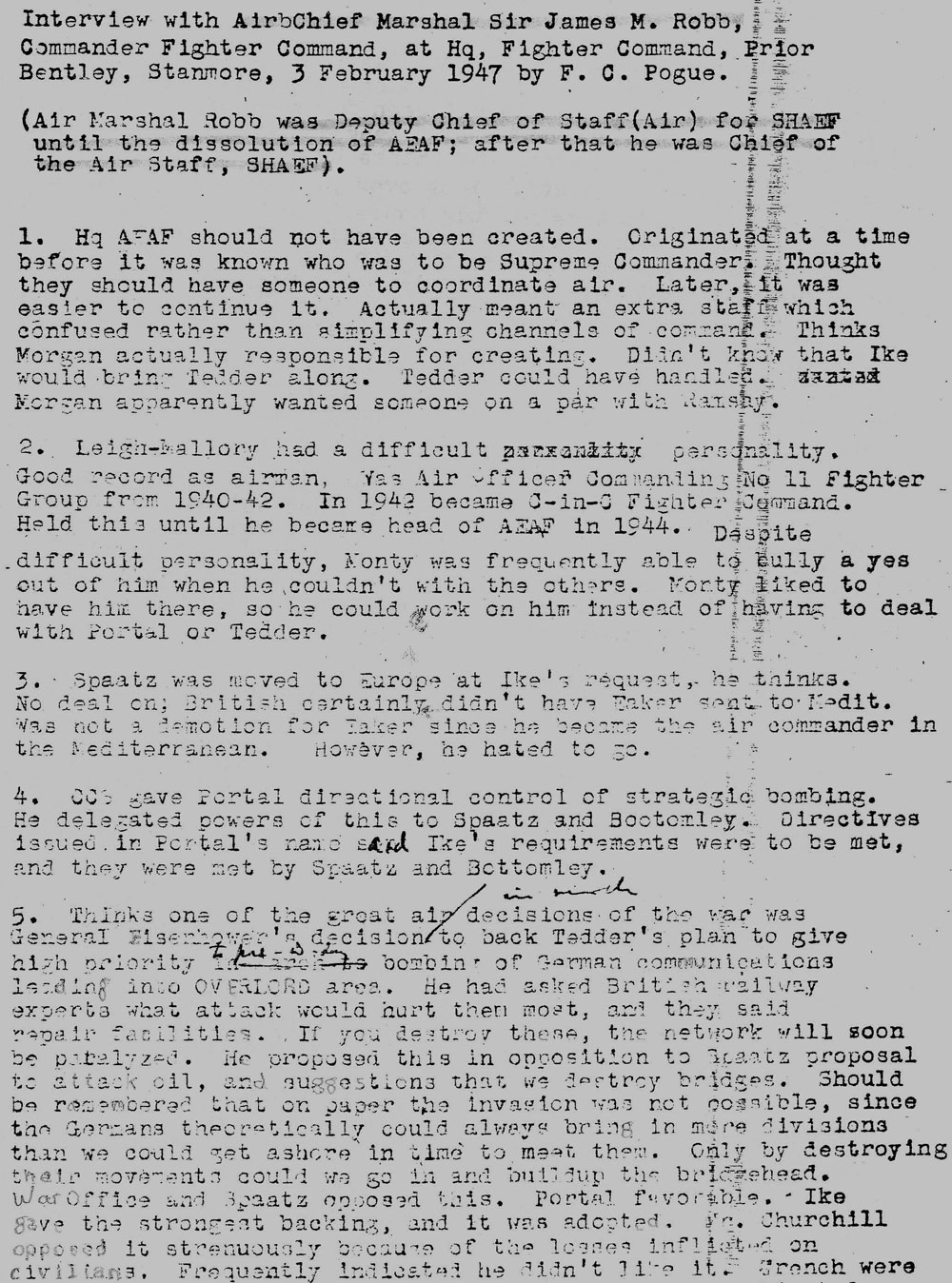

Ike had foreseen the acrimony in January 1944 when he declared, “I suspect that the use of these [strategic] air forces for the necessary preparatory phase will be particularly resisted.” Resisted so vehemently, in fact, that Ike would eventually threaten resignation, and the dispute would climb all the way to the White House and Downing Street. Spaatz and Harris, focused primarily on their mission of wrecking German industry, annihilating the Luftwaffe, and undermining enemy morale by ruthless air bombardment of Germany, regarded OVERLORD as a distraction and strove to minimize their commitment to it. Indeed, Spaatz once blurted indiscreetly at a staff meeting, “This [expletive] invasion can’t succeed, and I don’t want any part of the blame. After it fails, we can show them how we can win by bombing.” For an unspecified interval before the invasion, OVERLORD stipulated that the bombers would be controlled by Ike’s chief airman at SHAEF, Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, but Spaatz brusquely pronounced to Ike, “I have no confidence in Leigh-Mallory’s ability to handle the job.” Ike deftly addressed that issue to Spaatz’s satisfaction by rearranging his chain of command so that his much more likeable deputy, Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder of the RAF, would supervise strategic air matters.

But that Band-Aid solution failed to address the much more important matter of how bombers would actually support OVERLORD. Convinced that destruction of Germany’s oil industry would cripple the German Army and, in due course, the entire Nazi state, Spaatz fervently resisted the “Transportation Plan” scheme devised by the renowned British sage, Solly Zuckerman, who contended that heavy air attacks on French railroads and marshaling yards would isolate the Normandy battlefield and paralyze the enemy’s reaction to the invasion. Ike crossed his friend Spaatz by admitting that he favored Zuckerman’s idea, noting in an overseas cable to General Marshall, “There is no other way in which the tremendous air force can help us during the preparatory period to get ashore and stay there.” As for Spaatz’s claims about oil, Tedder quipped, “We have been led up the garden path before.”

An appalled Churchill, however, asserted that such attacks would “smear the good name of the Royal Air Force” by causing French civilian casualties as high as 160,000, according to one estimate. Precautions would minimize civilian losses, Ike insisted, but Churchill implored Roosevelt to abandon the plan and thereby avoid “a legacy of hate.” FDR replied, “However regrettable the attendant loss of civilian lives is, I am not prepared to impose from this distance any restriction on military action by the responsible commanders.”

It would therefore be the Transportation Plan; from mid-April to early June 1944, with swelling intensity, Allied air forces carried out attacks against the French railroad network, casting it into “complete chaos,” according to one report. Nearly 5,000 civilians died in those air attacks, surely a lamentable number, but far short of the 160,000 predicted in worst-case scenarios. On the eve of D-Day, a SHAEF operations summary observed: “The preparatory air phase of the OVERLORD campaign is now almost complete. . . . Though we already know that in certain respects success has been achieved, the ultimate test is to come.”

A copy of a February 3, 1947, interview of Air Marshal James Robb of the RAF by the U.S. Army historian Forrest Pogue, author of The Supreme Command volume in the U.S. Army’s World War II official history. Robb was one of Ike’s senior SHAEF airmen. In note 5 at the bottom of the page, Pogue remarks that Robb “thinks one of the great air decisions of the war was General Eisenhower’s decision (in March) to back Tedder’s plan to give high priority to pre-D-Day bombing of German communications leading into OVERLORD area.” (Military History Institute, Pogue Papers, Carlisle Barracks, PA.)

Joseph Balkoski, who served for many years as the command historian for the Maryland National Guard and the U.S. Army’s 29th Infantry Division, is the author of Omaha Beach and Utah Beach, a two-volume account of the American involvement in the D-Day invasion. More than twenty-five years ago, he began work on a five-volume series about the 29th Division’s service in World War II. The first book in that series, Beyond the Beachhead, was published in 1989 and has been in print continuously ever since. The fourth volume, Our Tortured Souls, was published in 2013. Joe currently runs the 29th Division’s archives and museum in Baltimore, Maryland. He conducts battlefield staff rides in the United States and Europe for current U.S. Army soldiers as part of their military training and was recently recognized by USA Today as “the top living D-Day historian.”

comments powered by Disqus