“I COULD CHEERFULLY SHOOT THE OFFENDER”

OVERLORD Security Measures

by Joseph Balkoski

Posted March 31, 2014

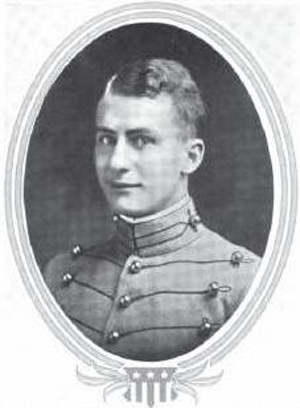

In April 1944 the restaurant in Claridge’s, the renowned Mayfair hotel just blocks away from Ike’s London headquarters at 20 Grosvenor Square, was not a good spot for an American general to gossip about D-Day. At an April 18 party thrown for Red Cross nurses by the U.S. Army’s chief intelligence officer in Britain, Brigadier General Edwin Sibert, a <em>Time</em> reporter noted: “Cocktails were sipped”—perhaps in sufficient quantities to loosen the tongue of Major General Henry Miller, the head of Ninth Air Force’s Service Command. The fifty-three-year-old Miller, nicknamed “Izzy” at West Point, was described by 1915 classmate Ike Eisenhower as an “old and warm friend,” but that friendship was about to disintegrate. Miller later swore to Ike that he had done nothing wrong, but three witnesses—one of whom was Sibert—noted that they had heard Miller in discussion with some nurses pronounce loudly and authoritatively: “Upon my honor, the invasion will come before June 15.” Sent home at reduced rank for that one-sentence breach of security, Miller was no longer in uniform by November. “I get so angry,” Ike cabled Marshall about this and other security lapses, “that I could cheerfully shoot the offender myself.”

Ike’s proclivity to chain-smoke surely worsened when he contemplated the impact of security slipups on OVERLORD. If the Germans could crack the Allies’ wall of secrecy—even just a day or two before D-Day—their ability to turn back the invasion would expand by a significant factor, and as Ike well understood, a defeat in Normandy would cast the Anglo-American war effort into chaos. Inevitably, Eisenhowerwould have to let hundreds of thousands of men in on the secret: how could ruinous security blunders possibly be averted?

The West Point class of 1915 graduation photo of Henry J. F. Miller, who would achieve major general rank and serve with the U.S. Ninth Air Force prior to D-Day. His classmate, Dwight Eisenhower, sent Miller home to the States at reduced rank following an April 1944 security violation at Claridge’s hotel in London. (29th Infantry Division Archives)

They would be averted by means of a new and highly restrictive security classification known as <em>Bigot</em>. Only those issued <em>Bigot</em> ID cards would be informed of the OVERLORD secret and granted access to the locations—under twenty-four-hour guard—where invasion plans were secured. The minuscule number of <em>Bigots</em> in early 1944 swelled as SHAEF disseminated OVERLORD documents to the units tasked to carry out the mission; ultimately, when 150,000 assault troops were briefed in the fortnight preceding the invasion on their hour-by-hour D-Day roles, the top brass restricted them to marshaling areas, known as “sausages” due to their appearance on maps. Formidable coils of concertina wire sealed the GIs and Tommies inside, where stern Counter Intelligence Corps men censored letters—which would not be mailed until after D-Day in any case—and ensured no conversations would take place with inquisitive locals approaching the wire. Presently escape from this miserable cooped-up existence would come: troops would depart the sausages; march like humpbacks overloaded with equipment through the verdant English countryside, fragrant with foxglove and Queen Anne’s lace; and proceed to the ships or airplanes that would carry them across the Channel to meet their fates in Normandy.

Enforcing secrecy among military personnel was straightforward; to address the much thornier issue of civilian security, Churchill created a committee headed by a sixty-five-year-old former Indian civil servant named Sir Findlater Stewart. Among the recommendations made by Stewart’s committee and later adopted by the British war cabinet were restrictions that made travel between Britain and neutral countries, particularly Ireland, difficult if not impossible; prohibitions on neutral diplomats’ movements and correspondence; and a travel ban starting on April 1, 1944, by British civilians to England’s five-hundred-mile southern and southeastern coastline from Land’s End to East Anglia, an injunction that Stewart estimated would impact 600,000 people per month.

When some civilian ministers, including Churchill, protested against the sweeping zone that would be prohibited to British citizens—“We must beware of handing out irksome for irksome’s sake,” the prime minister avowed—the committee churned out a one-page list for Churchill of the top secret D-Day equipment that would in all likelihood no longer be secret if the travel ban was not imposed, including Mulberry artificial harbors, Duplex Drive amphibious tanks, and the underwater pipeline code-named PLUTO.

True, the rules would inconvenience everyone, civilians, soldiers, diplomats, and politicians alike. But General Frederick Morgan, OVERLORD’s progenitor, provided a cogent defense for such stringent security: “If we fail, there won’t be any more politics,” he said.

A top secret Bigot map of Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy, just south of Omaha Beach. Only personnel possessing Bigot ID cards could view this map. U.S. 1st Infantry Division troops would secure this sector by the end of D-Day. The area just above “Vehicle Transit Area 4” is today the U.S. Military Cemetery at Omaha Beach. (29th Infantry Division Archives)

Joseph Balkoski, who served for many years as the command historian for the Maryland National Guard and the U.S. Army’s 29th Infantry Division, is the author of Omaha Beach and Utah Beach, a two-volume account of the American involvement in the D-Day invasion. More than twenty-five years ago, he began work on a five-volume series about the 29th Division’s service in World War II. The first book in that series, Beyond the Beachhead, was published in 1989 and has been in print continuously ever since. The fourth volume, Our Tortured Souls, was published in 2013. Joe currently runs the 29th Division’s archives and museum in Baltimore, Maryland. He conducts battlefield staff rides in the United States and Europe for current U.S. Army soldiers as part of their military training and was recently recognized by USA Today as “the top living D-Day historian.”

comments powered by Disqus