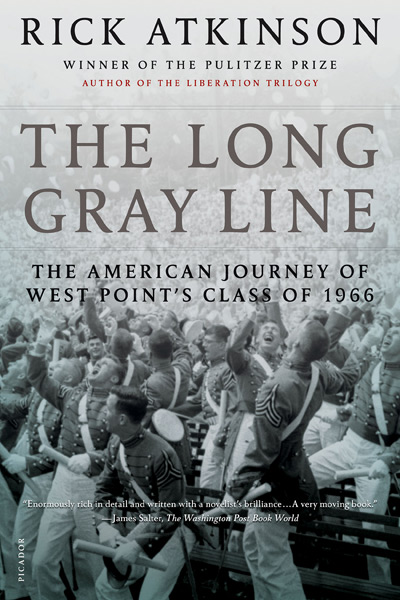

Excerpt from The Long Gray Line

You can download an excerpt of the book as a PDF file, or read below:

Chapter 1: BEAST

EVEN ON the Sabbath dawn Penn Station was a busy place. Redcaps hurried across the concourse on crepe soles, pushing carts piled high with luggage. Vendors began to unshutter their kiosks, and the garble of arrivals and departures droned from the public address system. Although it was a gray beginning to what would be a gray day, the huge waiting room was awash with a hazy luminance. Light seeped through the windows high overhead and filtered down through the intricate ironwork. Chandeliers, each with eight yellow globes, dangled from the girders. This was the year before the station — which had been modeled on the Baths of Caracalla — would be razed for a new Madison Square Garden and a monstrously ugly depot. Now, though, the building was magnificent, with its arches and trusses and vaulting space as vast as the nave of St. Peter’s.

Beneath the large sign proclaiming INCOMING TRAINS, five young men climbed the stairs from the grimy warren of tracks below. Each carried a small bag containing a shaving kit, a change of clothes, and, as instructed, “one pair of black low-quarter, plain-toe shoes.” They had boarded the train in Newport News and traveled north, through the pine forests of southern Virginia, through darkened Washington and Baltimore. Without much success, they had tried to nap as the train rocked through Maryland and the slumbering villages of southern New Jersey, silent except for the hysterical dinging of crossing gates. Now, a bit rumpled but excited by their arrival in Manhattan, the five chattered like schoolboys set loose on a great adventure.

They walked quickly across the waiting room toward Eighth Avenue. In front of a newsstand, the day’s edition of The New York Times had just arrived in a thick bundle. Under the paper’s name and the date — July i, 1962 — the front page offered a remarkable snapshot of an America that was about to vanish and the America that was about to replace it.

LEADERS OF U.S. AND MEXICO HAIL NEW ERA OF AMITY, the lead Story proclaimed. A large photo showed the president ignoring his Secret Service agents to grasp the hand of a boy on his father’s shoulders in Mexico City as a huge crowd — more than a million — roared, “Viva Kennedy!”

On the opposite side of the page, the Times reported that the federal deficit topped $7 billion as fiscal 1962 ended, with “the virtual certainty of another deficit” in the new fiscal year. Other articles reported that former President Eisenhower, speaking from his Gettysburg farm, had declared that Republicans represented the party of business and were “proud of the label”; Dodger southpaw Sandy Koufax had notched thirteen strikeouts in pitching a no-hitter against the Mets; and an article from Detroit — ’63 AUTOS TO ACCENT STYLING OVER THRIFT — noted that car makers were about to offer more chrome, automobiles two to seven inches longer than the previous year’s models, and ninety varieties of bucket seats. The Times also documented developments in Algerian politics, Saskatchewan health care, and a call by Nikita Khrushchev for the Soviet people to diversify their diets by eating more corn flakes. “Americans and Englishmen,” Khrushchev observed, “are masters of preparing corn in the form of flakes.” The missile gap had been succeeded by the cereal gap.

Tucked into the lower right-hand corner of page 1 were two nettlesome articles with an exotic dateline: Saigon. The first reported that the South Vietnamese government “charged today that new weapons from Communist China had been given to Communist guerrillas. It demanded action against these ‘flagrant violations’ of the Geneva agreement.” The second article said that “a massive combined operation against ‘hardcore’ Communist guerrillas along the Cambodian border has resulted in the discovery of two training camps for insurgents and the capture of enemy documents.” A related story on page 22 reported that “the most avidly read book in Saigon is Bend With the Wind, a breezy tract put out by the United States Embassy for the big American colony here.” The book contained advice on riots, invasions, coups, typhoons, and earthquakes; it also explained a sequence of alerts known as Conditions White, Gray, and Yellow. In the event of Condition Red — the most serious gradation — Americans were to “remain calm and prepare for evacuation.”

The five young men stepped onto Eighth Avenue. The overcast sky threatened drizzle; New York City looked hard and scruffy, as though it too had been shortchanged on sleep. They turned north and walked six blocks to the West Side bus terminal. A ticket agent directed them to the proper bus, whose sign above the windshield advised in block capitals WEST POINT. They climbed aboard.

All five were the sons of Army officers stationed at Fort Monroe, a picturesque antebellum fortress on the Chesapeake Bay where Jefferson Davis had been imprisoned after the Civil War. All five were also good students, model citizens, and active in extracurricular activities. One was an outstanding marksman, another a champion middleweight boxer.

The youngest of the group was still six months shy of his eighteenth birthday. Just under five feet ten inches tall, he had his mother’s blue eyes, high forehead, and fair hair. He laughed often, with an abrupt, high-pitched giggle that was easy to pick out in a crowded room. Although never a gifted athlete, he kept himself in good shape. His name was John Parsons Wheeler III, and he was nervous.

As the bus worked its way north through Manhattan, Jack Wheeler couldn’t help wondering whether he was making a mistake. He had agonized over where to go to college. The decision seemed so momentous that he had avoided making it for weeks after the arrival of the academy’s acceptance letter — Admission Form 5.413, dated 24 April 1962, which had declared him “fully qualified and entitled to admission.” At Hampton High School, he had been editor of the yearbook and president of the Spanish Club. His classmates considered him warm, erudite, and serious. The word among the girls at Hampton High was that if you planned to go out with Jack Wheeler, you had better be smart. He’d even lectured one of them on the constellations, pointing out the Dippers and the North Star. During his senior year, his classmates had voted him “most likely to succeed.”

Much of Jack’s ambivalence was caused by another letter he had received, this one dated April 16, 1962, and embossed with the Latin phrase Lux et Veritas: “Yale University takes pleasure in advising John Parsons Wheeler III that he has been approved for admission to the freshman class entering in September 1962.” Unlike West Point’s free education, four years at Yale were very expensive, but Jack had won a National Merit Scholarship to cover the cost. The idea of going to New Haven to study literature and live like a normal college student had enormous appeal. There was no doubt about where his mother, Janet, wanted him to go; she nudged him persistently toward Yale, convinced that her elder son needed a place that would give his mind free rein.

Just as persistently, his father nudged him toward West Point, his own alma mater. He very much wanted his son to be a military man: the Wheelers hailed from a long line of soldiers, traceable to at least the seventeenth century. But when young Jack took the physical examination for the academy, Army doctors disqualified him because of a punctured eardrum. Not to be denied, his father had taken him to an Air Force doctor who was accustomed to seeing shattered ears in his pilots. “Mighty fine ears your boy has, Colonel,” the doctor said cheerfully before certifying the young man as physically sound for the academy. As Colonel Wheeler pressed his campaign, Jack had to admit that West Point felt comfortable, like the succession of Army posts he was used to — Fort Riley, Fort Knox, Fort Hood, Fort Monroe. The academy would almost be like home.

When he had finally made up his mind, Jack came down to dinner one evening, pulled up to the table, and announced, “I’ve decided where I’m going to go.” He paused dramatically before adding, “West Point.” Janet finished her meal and excused herself. She got into the car and drove aimlessly around the post, trying to calm down. Without even bothering to check the marquee, she parked next to the theater, bought a ticket, and walked inside. “The most desirable woman in town and the easiest to find,” the poster next to the box office proclaimed; “just call BUtterfield 8.” By the time the heroine — played by Elizabeth Taylor — perished in an automobile wreck, Janet had recaptured her composure. She drove home and congratulated her son.

The bus rumbled across the George Washington Bridge and north onto Highway 9W, following the western Palisades. Past Upper Nyack, the land seemed to muscle up, inclining slightly as the engine whined through a shift of gears. Yes, West Point was a known quantity, more predictable than the alien civilian world of New Haven. The academy also offered an engineering education, which seemed more pragmatic to Jack than the humanities. In the aftermath of Sputnik, he thought, his generation had an obligation to keep America pre-eminent in the sciences and technology. That polished steel beachball, beeping its eerie A-flat taunt as it orbited the earth, had triggered a bout of American selfreproach several years earlier. The Soviets had humiliated the United States, and the implication was that the rising generation would have to set things right. Jack took that mission seriously, and West Point seemed a good place to accept the challenge.

Colonel Wheeler had not been around to see his firstborn off to West Point. Once again duty had taken him from home, this time to prepare for command of a tank battalion at Fort Riley, Kansas. Big Jack’s frequent absences stretched the emotional distance that Jack felt; the more his father was away, the more Jack craved his admiration and respect. He understood, perhaps intuitively rather than intellectually, that attending West Point was the surest way to please Big Jack.

With a few hours to kill before the train left for New York, Jack had paced restlessly through the house at Fort Monroe.

“Come on,” his mother said, sensing that he needed to get out, “let’s go have dinner at the Officers Club.” While they were eating, a general stopped by the table to chat for a moment. When he learned that Jack was leaving that night for the academy, the general put a hand on his shoulder and said gently, “He’s too young. Boys shouldn’t leave for soldiering so young.”

Finally the moment came and Janet drove her son to the Newport News station. It was a beautiful evening, the sky jammed with stars. At home in Laredo, Texas, during World War II, she had fallen into the habit of staring at the heavens, wondering whether her husband was alive or dead on some European battlefield. Now, hugging her son on the platform, she looked up again and silently prayed to her ancestors, Please, please attend him. His eyes flooded with tears; dry-eyed herself, she fought an impulse to hop on the train with him. With a last hug she whispered, “Go find your star, Jack.” And then he was gone.

Now, ninety minutes after leaving New York, the bus rolled into the village of Highland Falls, drowsy with summer and Sunday. Diners and pubs lined the main street, where five-and-dime stores peddled “Go Army!” pennants and ceramic figurines of cadets with little bow mouths and ruddy cheeks. Ahead lay the academy’s main entrance, Thayer Gate.

The sheaf of official documents Jack had received included a form letter with a veiled warning from the adjutant general: “You are to be congratulated on this opportunity for admission to the military academy, for it comes only to a select few of America’s youth .. . Now is the time for you to reconsider your decision to become a member of the Corps of Cadets. You should reassess your ambitions most conscientiously in the light of the mission of the academy, which is the training of young men for careers as officers in the regular Army of the United States. Without strong determination to achieve such a career, many of the demands of cadet life will be irksome and difficult.”

With a squeal of brakes, the bus pulled up to the Hotel Thayer. The young men stood up, yawning and stretching as they shuffled toward the door. Jack grabbed his bag and stepped onto the pavement, his full sense of high purpose tinged with a touch of dread.

The Thayer was an imposing brick hostel perched on a knoll above the Hudson. Its roof, like that of a castle, was ringed with battlements, and the lobby was often filled with old soldiers in various stages of fading away. The grand dining room featured octagonal pillars with gilded basrelief vines and tendrils that climbed toward the oak-beamed ceiling. Like all formal dining rooms on Army posts, this one smacked of the Old Army — big steaks and blue cheese and undertipping alcoholics. But little imagination was required in the soft lighting to see a MacArthur in the far corner, strands of hair combed vainly over his pate, or an Eisenhower with his eyebrow cocked, hanging fire with his cutlery as he listened to an old friend from ’15, the famous “class that stars fell on.”

Now, hundreds of young men, all as nervous as Jack, crowded the Thayer. Most had never seen the academy; a few had never been on a military post. Many — those with their hands still clamped over their wallets — had just come through New York for the first time. Nearly two-thirds were the sons of military fathers, and they came as close to constituting an American warrior caste as the nation would allow.

Two-thirds also were Protestants; only 1 percent were Jewish. Compared with other new college freshmen with whom they had been surveyed, the new cadets smoked less, prayed more, cribbed less, napped more. Few were from either very rich or very poor homes; half, in fact, came from families with annual incomes of $10,000 to $15,000. They inclined to achievement and overachievement: most had been varsity athletes, student government or class officers, and members of the National Honor Society. The Army brats, like Jack, had grown up as nomads, moving an average of eight or ten times in their young lives. The upbringing encouraged a strange concoction of traits that made them cosmopolitan and self-reliant, yet rootless and somewhat insulated from the larger civilian world.

All of them were also sons of the 1950s. Had they been asked, they collectively could have belted out the theme songs to the Mickey Mouse Club or the Davy Crockett show (“Born on a mountaintop in Tennessee …”). They had been nurtured on Wagon Train and Wyatt Earp, and knew that DDT meant “drop dead twice.” Most wore butch haircuts or flattops, and a few rebels had experimented by rolling their T-shirts above their biceps with cigarette packs secured in the sleeve. They universally admired John Glenn, another military man, whose three orbits earlier that year had earned him fame and glory; they agreed with Pablo Picasso, who had said of the smiling Marine from New Concord, Ohio, “I am as proud of him as if he were my brother.” Finally, they were largely ignorant of many things, including women, failure, and evil.

Jack spied a familiar face in the crowd, a friendly, reassuring one. Jeff Rogers, whose father and uncle were both West Pointers, had graduated from Hampton High in 1961 and enlisted in the Army. He had spent the past year at the military academy prep school in Virginia, brushing up his math skills and memorizing thirty new words a week. As little boys at Fort Riley, Jack and Jeff had played in the same sandbox; their fathers had both been brown-boot cavalrymen who made the necessary transition to tanks during World War II.

“C’mon,” Jeff said, after pumping Jack’s hand, “let’s go look around.” They strolled down to the river and past the old train station, a pretty little gingerbread building with gables and a steep slate roof. Jack saw sailboats tied up nearby — that also was reassuring. At Fort Monroe, the Wheelers lived in a three-bedroom house near the sea wall, where they were lulled by the slap of Chesapeake waves on the stones. The commanding general occasionally let the family borrow his boat and Jack had learned to sail on the bay. The Hudson, he thought, with its tides, current, and barge traffic, would provide a stiff challenge to his seamanship.

The river was also beautiful. During the Ice Age, a mile-thick tongue of glacial ice had pushed through here, notching a gap in the steep highlands. To the south, Jack and Jeff could see where the gorge cut between Bear Mountain on the west bank and Anthony’s Nose on the east. To the north, the river sliced through another pass bracketed by Storm King Mountain and Breakneck Ridge. Henry Hudson and his sullen crew had threaded this strait aboard the eighty-ton Half Moon on September 14, 1609, futilely searching for passage to the western ocean. Later that century, Captain Kidd and other pirates had infested the river. Even now, after more than three hundred years of encroaching civilization, the gorge still held a pristine, New World charm.

During the Revolution, George Washington had pronounced the military garrison at West Point “the most important post in America.” To safeguard the fort against the British, Washington entrusted its command to a man whose name became a synonym for treason. Benedict Arnold was swarthy, doughy, and given to duels; in 1780, he was also the finest warrior in the American Army, gallant at Ticonderoga, fearless at Quebec, badly injured at Saratoga. For six thousand pounds sterling, Arnold agreed to sell West Point’s fortification plans to the British, who waited downriver with an assault force. Full of ill temper over perceived slights, and influenced by his new wife, Peggy, the daughter of a Philadelphia Tory, Arnold slipped the plans to a British spy, Major John Andre. But when Andre was captured and the incriminating papers discovered in his boot, the plot collapsed. Arnold galloped to his barge — Jack could see the precise spot across the Hudson — and ordered eight of his men to row him downriver to the British sloop Vulture. The traitor fled to London, but West Point was saved.

Jack and Jeff climbed up the steep hill from the train station and through the stone portal that led to the Plain. This was the precise path that Douglas MacArthur, after arriving on the West Shore Railroad, had walked sixty-three years earlier, towing his indomitable mother. She had ensconced herself for four years at the West Point Hotel — now gone — where she could clearly see room 11×3 in the barracks and tell by the lamplight whether young Doug was studying.

Now, the orderly splendor of the Plain lay before the two young men. From the river bluff, the plateau ran west for half a mile before suddenly lifting into the dark green hills. Barracks, houses, and academic buildings ringed the parade ground. Jack felt excitement rising through his anxiety. West Point was a grand place, he thought, wonderfully laden with tradition and honor.

Afternoon shadows began to lengthen. The time had come to return to the Thayer. An arduous first day lay ahead, and both of them wanted to get a good night’s sleep. Leaving the Plain, they passed the Patton monument. It was said that, as a boy, George had hauled a chicken carcass around his house to mimic Achilles dragging Hector around the walls of Troy. The statue here depicted a barrel-chested warrior with broad hips and a nose like the prow of a ship. Clutching his binoculars in both hands, a pistol the size of an anvil on each hip, he had become the American Achilles.

One day when he was in the sixth grade, Jack had discovered his father’s binocular case in a closet. Inside the container he found ghastly black-and-white photographs of a concentration camp near Nordhausen that Big Jack had helped to liberate in 1945. Jack, who rarely showed much interest in his father’s wartime adventures, had been shocked — and fascinated — by the images of the skeletal dead and the skeletal living. He was proud that his dad had fought to crush that kind of horror. Even so, the photos were fearsome. But warriors, he suspected, had to get used to fearsome sights. That was part of their trade, part of the initiation into the brotherhood of combat.

Returning to the Thayer, Jack and Jeff had Patton’s advice to contemplate. “Pursue the enemy with the utmost audacity,” the great battle captain warned, in words inscribed at the foot of his monument. “Never take counsel of your fears.”

“Sir, New Cadet Wheeler reports to the man in the red sash, as ordered!” Jack stood with his shoulders squared, eyes fixed on the glowering upperclassman in white gloves, white hat, and red sash.

“Drop the bag!”

Jack was ready. He instantly let his valise fall to the pavement. Around him in Central Area he could hear upperclassmen verbally mauling other classmates who failed to demonstrate sufficient alacrity.

“I said drop the bag, NOW! When I tell you something, you are to do it immediately. Do you understand?”

“I understand.”

“Wrong, you dumb crot. The correct answer is ‘yes, sir.’ You are permitted only three answers: Yes, sir. No, sir. No excuse, sir.”

“Yes, sir.”

The ordeal had begun and it was instantly dreadful. The first two months of cadet life were known as Beast Barracks. Jack and his class mates would not even be plebes until September; for now, they were simply “new cadets.” For the next eight weeks they would be treated like vermin by the small cadre of upperclassmen who had been left behind for the summer to supervise Beast. The physical and psychological stress was intended to weed out the weak and unworthy, beginning with this lesson in instant obedience.

The overarching question at the Thayer that Monday morning, July 1, 1962, had been whether it was best to report early or late within the eight A.M. to ten A.M. period allowed them on R-Day — Reception Day. Some cadets who had not come up to West Point the night before were just now arriving — including one who stepped out of a limousine owned by his baroness aunt. For breakfast, Jack had walked into Highland Falls to a diner, where he swallowed some coffee and picked at his Danish. When he could no longer stand the tension, he hurried back to the Thayer, retrieved his bag, and climbed onto a shuttle displaying a large white sign: NEW CADET BUS.

Even before ten o’clock the casualty list began to grow. One lanky teenager reported with a tennis racquet and a set of golf clubs over his shoulder; after a five-minute torrent of abuse from an outraged upperclassman, he executed a smart about-face and walked back to the Thayer for a ride home. Others had arrived without realizing that they owed the Army four years of active duty service following their four years at West Point. Those who had been in the Army — the “prior service” cadets like Jeff Rogers — and the Army brats like Jack Wheeler were better prepared, thanks to careful coaching by their fathers and friends. Yet the intensity of disdain from the upper-class cadre, who barked and shrieked until spittle flecked the faces of the pathetic creatures cowering before them, was unnerving.

R-Day was also a masterpiece of logistics, planned with lavish attention to detail. The man in the red sash directed Jack to the gymnasium, where he was weighed, measured, inoculated, and judged in pull-ups, push-ups, and how far he could fling a basketball while kneeling. He surrendered all of his cash — $16 — and ran to the barbershop, where he was scalped so rigorously that the contours of his skull could be read like a topographical map. He then was photographed and issued an identification card.

On the fourth floor of the cadet store, a tailor measured him for tight fitting dress trousers. (In an earlier age the tailor asked new cadets whether they “dressed right or dressed left” — that is, whether they preferred to tuck their genitals into the right pants leg or the left). In the basement of the store, Jack received one cadet raincoat, two sweat suits, and two gray shirts. In the boxing room of the gymnasium he picked up eight pairs of cotton gloves, bathing trunks, two pairs of gym shorts, one bathrobe, twelve cotton undershirts, four white waist belts, eight white shoulder belts, two pairs of black socks, three white twill shirts, two pairs of suspenders, and a stack of white boxer shorts, known as drollies. Not least among the culture shocks for those who had spent their lives clad in snug cotton briefs was this required conversion to the baggy drollies.

On and on it went, hundreds of sweating, confused cadets dashing about like so many sheep, the white-gloved upperclassmen nipping at their heels. In the south boxing room of the gym, Jack collected a pair of uniform shoes, a pair of rubber overshoes, leather slippers, low-cut Keds, canvas basketball shoes, shower slippers, and a pair of shoe trees. He also received a gray uniform cap, two garrison caps, two fatigue caps, and a blue rubber rain cover for his uniform hat.

The academy divided the 807 new cadets into six companies, each of which was further split into four platoons. Each platoon contained four squads, with eight cadets per squad. The cadet barracks — known as Central, North, Old South, and the just-completed New South — stood in “divisions,” built like row houses. A division contained four floors, with four rooms on a floor. The academy did not issue keys — honorable men, after all, had no need for locks — and many cadets who had forgotten their room numbers wandered about the division corridors, too frightened to acknowledge their negligence. Although the divisions abutted, new cadets could pass between them only by going through basement corridors, where the bathrooms, or “sinks,” were located, or by exiting the front door of one division and entering the door of another. Only upperclassmen were permitted to travel along the stoops, the broad porches lining the division fronts.

The morning passed with numbing celerity. Jack found that he was assigned to the fourth platoon of Third New Cadet Company. His room, number 1732, measured roughly twenty by twelve feet, with large windows, a linoleum floor, and a small, spare alcove containing three cots. His father’s old room lay diagonally across Central Area.

I can’t believe this is happening to me, Jack thought as he stood by the window. For a moment he felt as though he were living outside his body, watching himself. The sight was not a pretty one. Sweat poured from his shorn scalp and cascaded down his forehead. An odor of new wool and new cotton filled the barracks, as distinctive as the upholstery smell in a new car. Everything seemed hazy, unreal. Is this really happening? he asked himself again. He already had amassed enough gear to outfit the Wehrmacht, yet there was another heap of equipment on his bunk. He stared at the pile. I know what that is, he thought; that’s a helmet. That’s a helmet liner. That’s a poncho. That’s a web belt. This is serious. This is the Army.

He hustled down to the orderly room in the barracks to collect a can of Brasso, a glass tumbler, linseed oil for his rifle stock, and a bag with fifty other odds and ends. Back in the room, he stared again at the intimidating mound on his bunk. Where would he put all this stuff? Clearly, every item belonged in a particular niche. West Point, evincing a rage for order, resembled a fine watch; each tiny part had its proper function and position. Disarray was calamitous. When cadets laid out their field equipment during an inspection, for instance, the pistol belt was to go at the top of the display, the gas mask at the bottom, the poncho at left center. There was a right way, a wrong way, and the West Point way.

Compulsive order also governed the barracks. “All books,” according to one regulation, “should be pushed to the back of the shelves and not be placed tangent to the edges.” Even the medicine cabinet possessed an inviolable harmony. Hairbrush, soap dish, and razor on top; toothbrush and toothpaste in the middle; shaving cream, deodorant, and water glass at the bottom.

Jack scrutinized the uniform list he had been given. The document comprised three single-spaced pages of required articles, including “belt, cartridge or pistol; belt, guidon bearer; belt, saber; belt, uniform; belt, white shoulder; belt, white waist.” A separate, five-page dress code manual catalogued the appropriate uniform for every conceivable activity. The manual told him what to wear to the bowling alley, to the barbershop, to the movies, to model airplane clubs, to the telegraph office, even to a fire (“any uniform authorized for wear outside of barracks”). The document told him what to wear to a court-martial if he was a witness; it told him what to wear if he was a defendant. It told him that the long overcoat “will be worn to chapel, to review, and to inspection” and that “the short overcoat will be worn when the long overcoat is not prescribed.” Implicitly, it told him that he had checked his free will at Thayer Gate.

“Let’s go, everybody out in Central Area. Let’s go. Gonna learn how to march, New Cadets.” The squad leader moved through the barracks, barking commands.

Jack hurried into the hall and down the stairs, keeping to the outer wall of the stairwell, as required of new cadets and plebes.

“Rack that neck in, mister. You call that bracing?”

Jack jerked his head back. Except when they were in their rooms or in the showers, new cadets were required to “brace” by retracting their necks into their collarbones in what appeared to be an awful orthopedic affliction.

“Rack your neck in, smack,” the upperclassman ordered again. “I want to see six wrinkles in that neck. Six wrinkles, come on. One, two, three, four, five, six — good — seven. Oh my God, seven wrinkles. Come look at this, Jim. Seven wrinkles. That’s a new record. Congratulations, smack.”

Jack and his squad mates stood braced in front of the 17th Division. Sunday’s overcast had blown over, revealing a fine summer day, temperature in the mid 80s. Dressed in long-sleeve wool shirts, the cadets sweated like dray horses. Throughout Central Area, hundreds of other new cadets stood before their divisions, braced and sweating.

“All right, we’re going to practice saluting. Show me a salute.”

Jack lifted his right hand to his right eyebrow and returned it to his side.

“That looks like a damned parachute coming off your forehead, mister. Make it snappy. Do not, repeat, do not move your head into the salute.”

Standing in the sun, they practiced saluting and the rudiments of marching. “The fundamentals of drill are established daily,” Frederick the Great had proclaimed, and West Point took him to heart. “If these maneuvers are all accurately observed and practiced every day, then the army will remain virtually undefeatable and always awe-inspiring.”

The cadre taught the new cadets to stand at attention with heels together and toes pointed out at a 4 5-degree angle. At the command of “for-ward,” the men shifted their weight inconspicuously onto the right foot; at the subsequent command of “march,” they stepped with the left foot. Proper marching required a thirty-inch step, arms swinging without bending at the elbow.

Left-face, right-face, about-face, column left, column right. After an hour of drilling they remained ragged, still a far cry from Frederick’s “awe-inspiring.” But for now it would have to do. The hands on the large clock near the 1st Division crept toward five P.M. The time had come to take the oath.

The commandant stood waiting. As he watched from Trophy Point, Brigadier General Richard G. Stilwell saw the new cadets marching toward him across the Plain for the traditional swearing-in. They weren’t exactly the Coldstream Guards. But considering that the academy had owned them for only seven hours, they looked more like soldiers than anyone would have thought possible that morning.

A small crowd of parents also waited. The ceremony always provided a good show: mothers weeping, fathers beaming, cadets glassy-eyed with fear. Trophy Point had long been a favorite spot at West Point. The sweeping vista of the river had even been popular among French wall paper manufacturers, who reproduced the view on Parisian salon walls in the early nineteenth century. Now the promontory was dominated by Battle Monument, a huge shaft of granite dedicated to “the officers and men of the regular Army of the United States who fell in battle during the War of the Rebellion.” Fifty captured Confederate cannons had been melted down to cast the plaque on the monument.

A statue of Fame, arms raised high in triumph, crowned the shaft. The bosomy, winged figure supposedly was modeled on Evelyn Nesbit, a one-time chorus girl whose jealous husband had murdered her lover, the corpulent rake Stanford White, after she confessed to frolicking naked on a red velvet swing in White’s love nest. Trophy Point also bristled with cannons, most of them captured during the Mexican War. And there were sixteen links displayed from the Great Chain, the barrier that had stretched across the Hudson during the Revolution to prevent the British fleet from severing New England from the other colonies.

On a summer day in 1934, Richard Stilwell had walked across the Plain to swear his allegiance here. He had been a poor boy from Buffalo; his father, a milkman, died when Richard was an infant. His mother remarried a cable splicer for the phone company, a man who spent a good deal of his life in manholes, soldering breaks. After a year at Brown, where he earned his tuition by working the graveyard shift in a bakery, Stilwell was offered an appointment to the academy. He leaped at the chance of a free education and an opportunity to raise himself. He had loved West Point from the first day of Beast and even now cherished the memories of his cadet years. “To describe Pinkie with one expression,” the 1938 yearbook said of Stilwell, “we would say he has selfconfidence to the «th degree.” Years later, after he had served as chief of staff for the Military Assistance Command in Vietnam, he would also be described by one historian as having “an unwavering trust in authority that led him to place loyalty to superiors above other considerations.”

Stilwell’s peers considered him one of the most brilliant officers in the Army, with a tough, penetrating gaze that made lesser men squirm. Blond and stocky, he was addicted to work and occasionally spent the night in his office, stretching out on the floor or leaning over his desk for rest. Dick Stilwell was the kind of man who learned a new word every day and then actually used it gracefully in conversation. He had been at West Point for three years now; as second in command, he helped bridge the transition from the previous superintendent, the great reformer Gar Davidson, and the current supe, an up-and-comer named

William Childs Westmoreland. Stilwell had not really known West moreland before i960, though they had crossed paths briefly in Normandy during World War II and again in Tokyo during the Korean War. Although the new superintendent lacked Davidson’s intellect, Stilwell believed that Westmoreland was smart enough to leave alone those things which were working well and to focus on external matters, such as plans to double the size of the corps.

Stilwell looked forward to returning to the muddy-boot Army — he had less than a year to go in his tour at the academy — but he had enjoyed his tour as commandant. Despite West Point’s isolation, or perhaps because of it, the world seemed to beat a path to the academy portals. Just that spring, William Faulkner, in one of the last public appearances before his death, had visited for two days in April, reading from The Reivers in his tweeds and ruminating on man’s destiny in “a ramshackle world.” Three weeks after that, MacArthur had delivered his famous valedictory, which still had the academy buzzing.

Then, just last month, John Kennedy came to address the graduating class of 1962. After landing in his helicopter on the Plain, right where the new cadets now marched, he had been whisked straight to the fieldhouse. The date, June 6, marked the eighteenth anniversary of D-Day, and the president had been in top form: bantering, sophisticated, masculine in this fortress of masculinity, a war hero among future war heroes. After hinting at his own re-election plans and making a pitch for the Army’s Special Forces — his beloved Green Berets — Kennedy made two specific references to the communist insurgency in Vietnam.

“I know,” he said, “that many of you may feel, and many of our citizens may feel, that in these days of the nuclear age, when war may last in its final form a day or two or three days before much of the world is burned up, your service to your country will be only standing and waiting. Nothing, of course, could be further from the truth.”

Instead, a new type of war threatened freedom lovers, the president continued, a conflict “new in its intensity, ancient in its origin — war by guerrillas, subversives, insurgents, assassins, war by ambush instead of by combat, by infiltration instead of by aggression, seeking victory by eroding and exhausting the enemy instead of engaging him . . . These are the kinds of challenges that will be before us in the next decade if freedom is to be saved, a whole new kind of strategy, a wholly different kind of force, and therefore a new and wholly different kind of military training.”

He had finished by recalling “the lines found in an old sentry box in Gibraltar: ‘God and the soldier all men adore, in time of trouble and no more. For when war is over and all things righted, God is neglected and the old soldier slighted.’ But you have one satisfaction, however difficult those days may be: when you are asked by a president of the United States or by any other American what you are doing for your country, no man’s answer will be clearer than your own.”

It was good stuff, precisely in line with Stilwell’s own philosophy, which he had developed during a somewhat unorthodox career that included a stint with the CIA in the 1940s. These new cadets are lucky, Stilwell thought. They have a mission again; JFK had made that clear. Only six years earlier, Eisenhower complained that the Army appeared “bewildered.” That was true enough. Nuclear weapons had seemed to make a large land force obsolete, and no one was certain what an army was for. But JFK knew: nation building, fighting insurgencies, providing officers who were warriors and statesmen — that was the Army’s new role. After years in the wilderness, the American Army was back.

The cadets had arrived at Trophy Point, ruddy and damp in their new wool uniforms. This class was much larger than Stilwell’s had been, twice the size in fact. He sometimes thought that ’38 had been among the last of the close-knit classes, more introspective, more isolated, and thus more tightly bonded. Of course, four years from now the class of 1966 would be considerably reduced. In a few days the commandant would gather them in South Auditorium and pull one of his favorite stunts. Scanning the group, he would gesture to about one third of the class. “You,” he would command, “everyone over here, stand up.” When they were on their feet, the general would say, “That’s how many of you will be gone by June 1966.”

Stilwell had a great deal to say now, but this was a time for brevity. The cadets were too shell-shocked to absorb much. If he did nothing else before he left West Point next spring, the commandant wanted to make them understand that in the twenty years ahead they were likely to face a confusing arra)i of assignments, circumstances, and predicaments. Their education at West Point would be one of the most important factors in determining how well they coped with the future. He was also convinced — and had said so publicly — that all of them were likely to be involved in Southeast Asia. Kennedy’s speech had reinforced that conviction. Such discussions, however, were better saved for a later occasion.

As Stilwell stood at the podium, the cadets formed neat ranks near Execution Hollow, where deserters and other miscreants had been hanged during the Revolution. The commandant began by welcoming them into “the noblest of professions — the military service of our country.” They had “been examined and stamped as raw material of passable grade.” They would be “tested, retested, [and] tested again” to determine whether they possessed the mettle to be worthy of the corps.

“As was true for all of the Z4,4oo who have preceded you, this has been a day none of you will ever forget. It has been a tough one, and designedly so. There will be many others. West Point is tough! It is tough in the same way that war is tough. It calls for leaders who can stand straight and unyielding under the sternest of physical and moral pressures. The security of this nation cannot be entrusted to men of lesser mold.”

They were apprentices, he continued. For the next year they would be annealed in a system that presumed one basic leadership principle: “If you can’t learn to obey orders, explicitly, you will never be able to give orders properly.

“My constant theme, sirs,” he concluded, “is that the history of the United States of America and the history of the United States Army and the history of the United States Military Academy are so closely intertwined as to be inextricable, one from the other. As goes the Army, so goes the nation.”

Stilwell let that sink in for a moment. The huge green shoulder of Storm King Mountain loomed behind him. “Men of ’66, your great adventure is under way. Now raise your right hand.”

Amid a forest of hands, Jack Wheeler lifted his. He had removed the white glove and was holding it, as the upperclassmen instructed, in his left hand. “I, John P. Wheeler, do solemnly swear that I will support the Constitution of the United States and bear true allegiance to the national government; that I will maintain and defend the sovereignty of the United States, paramount to any and all allegiance, sovereignty, or fealty I may owe to any state or country whatsoever.”

The oath taking for new military recruits was a ritual dating to the Roman sacramentum. But the larger ritual, a nation offering its sons in defense of the commonweal, was at least as old as Homer. With their newly acquired ability to about-face, the cadets turned and marched back to the barracks. None knew, none could possibly know, that his advance to the crest of Trophy Point had been the high-water mark of pax Americana.

Night crept gradually into the valley. Even when taps blew at ten o’clock, fingers of light lingered in the west. Bats skimmed the Hudson, trolling for insects. Mist coiled on the water, and across the river a soft orange glow seeped from one of the mansions set into the hills above the village of Garrison. Passenger trains periodically clattered along the far bank, their caboose lights burning red in retreat toward Poughkeepsie.

In the darkened barracks, most of the cadets were too exhausted even for regret. In room 1732, Jack Wheeler, wearing his new Army-issue Tshirt and the unfamiliar drollies, ruefully concluded that he had never in his life hustled through a more stressful day. The place required a curious humiliation of its initiates. Eight more weeks of Beast, then nine months as a plebe. Not every day could be this fatiguing, could it? Could it? They had even been required to scribble letters home and show the sealed envelopes to their squad leaders. Jack wrote:

Dear Folks:

Am fine. Must polish equipment. Also must write letter. Letter is written.

Love,

Jack

Five hundred yards to the east, barges worked the river, their deep hooting reminding the cadets that people remained free in the outside world, going and coming as they pleased, free to laugh, relax, slouch — yes, by God, even slouch. Only a day before they had been part of that world. Now they seemed to have been plucked from it forever. Never, the Patton statue had warned, never take counsel of your fears.

“Two minutes. Two minutes.” Thomas Merrit Carhart III listened to the stentorian voice of the King of Beast booming from the public address system. If that wasn’t the voice of God, it was as close to the Lord as most new cadets got in Beast Barracks. Tom fumbled with his name tag, trying to poke the pin through the flimsy blue bathrobe without impaling his thumb.

“One minute. One minute.” He raced out of the room and down the stairs of the 15th Division, remembering to wrench his head back into the braced position. Throughout Central Area he saw hundreds of his classmates, flip-flopping into formation in identical cotton robes and shower slippers. “Time’s up,” the King announced. A few stragglers scurried out of the barracks and into the ranks, pelted with abuse by the upperclassmen.

Tom’s squad leader strolled past, examining his charges. Since the beginning of Beast several weeks earlier these “clothing formations” had become a routine part of the hazing, but this was the first time that the entire battalion of new cadets was put through its paces simultaneously. The upperclassman in charge of the cadre — the King of Beast — would name a uniform and give them three or four minutes to change, police their rooms, and fall into ranks. The task seemed impossible, of course, and that was the point: the test of grace under pressure was considered vital in gauging the pluck of future combat commanders. The uniform combinations were endless: fifty-fifty, gym alpha, gym bravo, drill bravo, uniform sierra, uniform India, dress gray, full dress gray under arms, full-dress gray over white. Each outfit included a dozen accouterments

to clip, pin, button, or hook. Starched white trouser legs had to be pried open with a bayonet to avoid wrinkling them. Just getting the white cross belts to hang properly on the full dress grays was like tumbling into a cargo net.

Some preposterous mishaps had occurred, hilarious to everyone except the victim. When the order was first issued to wear white trousers under arms, several new cadets emerged from the barracks with their pants hoisted to the armpits instead of bringing their rifles. Some forgot their helmet liners so the steel pots drooped over their eyes, making them look like Beetle Bailey. John Oi, the Canton-born son of a Boston restaurateur, appeared in formation with his name tag upside down — IO — and was known forever after as Mr. Ten. Other cadets, after futilely fumbling with the little chain that was supposed to run across the tarbucket bill, had raced out with the links dangling beside their ears like a yeshiva boy’s curl. Years later, men who had been in horrific combat in Vietnam would wake up shrieking from nightmares — not that they were about to be overrun by the Viet Cong, but that they couldn’t find the proper hat during clothing formation.

“All right,” the King announced, his amplified voice echoing from the barracks walls. “You will now switch to uniform gym bravo. You have four minutes.”

Tom and his squad mates hurried back into the division. Gym bravo meant athletic shorts and shirt, jock strap, white socks, tennis shoes, and sweat suit. That required going down to the lockers in the basement sinks. The sinks had become a dreaded place, like the scene of a particularly vicious crime. Clothing formations often were succeeded by shower formations in the sinks. The upperclassmen forced new cadets to brace in bathrobes and shower togs. Sometimes the cadre backed a victim against a wall with a nickel wedged against the nape of his neck until he had squeezed out enough perspiration to make the coin stick to the tile. Or each cadet might have to “sweat a shadow” against the wall until the squad leader blew his whistle and ordered them all into an icy shower for two minutes.

For more than an hour the King of Beast kept the cadets sprinting in and out of the barracks. Seven times they changed their uniforms, even appearing once in the ludicrous ensemble of athletic shorts, Keds, full dress coats, and helmets. Finally, as the last light began to fade, the King dismissed the formation. Tom returned to his room, wearily picked up the clothes that lay strewn across the floor, and tumbled into bed.

The next afternoon, during a few minutes of free time, he sat near the window polishing his equipment. The relentless hazing had begun to wear him down, but the thrill he felt at being part of the Corps of Cadets had not yet dissipated. Arriving at West Point for R-Day had been the most exciting moment in Tom Carhart’s life; though rarely at a loss for words, he had been dumb struck with admiration for the upperclassmen strutting around the Hotel Thayer, their sleeves streaked with the chevrons of rank.

As a boy, Tom had been mesmerized by a television show called The West Point Story, which painted “that rockbound highland home” and her graduates — played by Clint Eastwood and Leonard Nimoy, among others — in hagiographic hues. What other school, he wondered, offered such an illustrious roll of graduates? Dwight Eisenhower, U. S. Grant, and Robert E. Lee. Stonewall Jackson, Black Jack Pershing, Jeb Stuart. The list also included Abner Doubleday, who had invented baseball, and James Allen, who discovered the sources of the Mississippi River, and George Goethals, supervisor of the Panama Canal construction. Some of the academy’s most praiseworthy sons were hardly known to the public, men like Leslie Groves, the bluff, stout engineer — described by one subordinate as “the biggest sonovabitch I’ve ever met in my life” — who had first supervised construction of the Pentagon and then commanded the Manhattan Project in World War II. Commandant Stilwell was right, Tom thought: the history of the Republic and the Army and West Point were inextricably bound, at least in those things most dashing and clever and glorious.

Tom wanted to be worthy of the great tradition, and while they were not especially glorious, he would start with his shoes. Squatting on the floor, he tried to see his face in the shine of his black low-quarters. Tom’s was a splendid face, actually, as he would have seen had the shine been better. Neither strikingly handsome nor painfully homely, his countenance was long and expressive, like one of El Greco’s Spanish noblemen, with thick lashes over blue eyes and a jaw that was firm but not pugnacious.

Tom also wanted to be spoony, which was defined in the glossary of cadet slang as “neat in personal appearance.” A good spit-shine didn’t come easily, and cadets relied on the prep school graduates in the class for helpful hints, such as how to use the proper side of an old T-shirt — the outside — and how to mix a little alcohol with the polish. But the alcohol tended to cloud in the sun, so it was important to rub cold water over the leather just before going outside. Tom now also knew how to tuck in a shirttail with the flat of his hand before positioning his trouser fly, belt buckle, and shirt seam in perfect vertical alignment. Brass looked best if he massaged in the Brasso with an index finger and then rinsed it off in scalding water. Being spoony, he now understood, was a demanding art.

Attending West Point was the fulfillment of a dream for Tom, and he longed to be the perfect cadet. That didn’t come easily — he was a scamp by nature — but he was working hard to repress his seditious streak. “At West Point, I have but one desire,” he had written on his academy application form. “To succeed, to do everything I do, no matter what it is, in the best way possible. I believe that anything someone wants he can have if he wants it bad enough. I want to be a success at West Point more than anything else. I believe I will be.” His efforts in Beast had already been noticed; the cadre had twice singled out Tom for honors, first as the best new cadet in his company one week, then as the best in Beast Barracks. In an effort to be a completely straight arrow, he had even reported himself for an honor violation when his parents, searching for a picnic spot during a weekend visit, unknowingly drove Tom down Lee Road in an area off limits to new cadets; after giving him a brief reprimand, the upperclassmen told him to forget the incident.

To be sure, some things at the academy disappointed him. The enforced letter writing to parents on Sunday nights seemed silly. One stormy Tuesday evening, his squad leader had staggered into the barracks, drunk and abusive, which to an eighteen-year-old Catholic virgin had seemed particularly offensive and disrespectful of the new cadets. And the mandatory dancing lessons for new cadets were nearly as humiliating as the clothing formations. A leather-lunged physical education instructor bellowed “one two THREE, one two THREE” as the cadets shuffled around the ballroom in Cullem Hall; sometimes the nearby women’s colleges supplied female partners — invariably short on pulchritude — but more typically the men blundered through the box step in one another’s arms, would-be officers dancing with would-be gentlemen.

Tom lacked the kind of pedigree that many of his classmates had. Some were second, third, and even fourth-generation West Pointers, like Jack Wheeler and John C. F. Tillson IV, both of whom, like Tom, had attended Virginia high schools. Tillson’s great-grandfather had graduated with the class of 1878 and served as provost marshal in Peking after the Boxer Rebellion. His grandfather, class of 1908, had served as a cavalryman at Fort Apache and elsewhere in the Southwest. Tillson’s father, class of ’38, was a major general.

Not having a bloodline like that sometimes nagged at Tom. Usually, though, he was proud and even boastful of being what he called “a lowborn, common-stock American mongrel,” the grandson of a farmer and a greengrocer. As such, he reflected the academy’s gradual tilt toward a more egalitarian corps. Smaller percentages of cadets now hailed from well-born Episcopal families; they were replaced by ever larger numbers

of Catholics and Baptists from the lower social ranks. Before World War I, the academy had drawn nearly a third of the corps from the families of doctors, lawyers, and other professionals. But by the mid1950s, sons of professionals made up only 10 percent of the cadets, and links to the upper class had been almost severed. West Point increasingly attracted military brats and sons of the working class.

Tom was both. His father had risen through the enlisted ranks of the Army Air Corps to earn a commission and his pilot’s wings; during World War II, he had flown P-38S in Italy. The Carhart family, including Tom and his four siblings, had traveled a typical Air Force circuit — Alabama; Washington, D.C.; France; Minnesota; and back to Washington. The father, Big Tom, who was well over six feet tall and weighed two hundred pounds, tended to leave daily decisions to his wife, a diminutive, pragmatic woman who would decide what kind of car to buy and where to send the children to school. Once, when he was a little boy, Tom had ridden a train with his mother and aunt to his grandmother’s house in upstate New York. Suddenly he spied an immense fortress of gray stone across the Hudson. “Look, Tommy,” his mother said, “that’s West Point up there. That’s a school for soldiers.”

“Can I go there?” the boy asked.

His aunt laughed. “Oh, Tommy, you could never go there. That’s for rich people.”

His mother, glancing archly at her sister, demurred. “You can go wherever you want,” she assured him. As the train sped north, the boy watched the gray walls recede to the south like an enchanting, hidden kingdom.

Tom assumed that he was Irish, but that was only three-quarters correct. The original Thomas Carhart immigrated to the New World from Cornwall, arriving in New York on August 25, 1683, as secretary to Colonel Thomas Dongan, the English royal governor. Awarded a16 5-acre tract on the south coast of Staten Island for his service, Thomas married a woman half his age, sired three sons, and promptly died. His will showed him to be a man of modest means. In addition to the land, he bequeathed a rapier, a pair of pistols “broken and out of order,” “six good pewter plates and twelve ould ones,” “an ould wagon,” and some household goods.

The family scattered, with some members thriving in New Jersey and both downstate and upstate New York. During the Revolution, the New Jersey Carharts fought valiantly for the rebels, the downstate Carharts remained loyal to the crown, and the upstate Carharts sat out the war as neutrals. Tom’s line was from Troy, upstate, but the neutrality must have been bred out in the subsequent two centuries. Tom Carhart remained neutral on very few issues. Like Jack Wheeler and scores of his classmates, Tom wanted to emulate his father by being an officer, gentleman, and war hero. He wanted to be a general.

Now, in the 15 th Division, he finally had a fair shine on his shoes. They looked spoony, if he did say so. After cleaning up the polish, he stood holding the small tin of dirty water. The container held only a couple of ounces, but there was no place in the room to dispose of them. Walking all the way down to the sinks was a nuisance, and he wasn’t prepared to drink the water, as some classmates did. Tom edged over to the window and peered outside. The roof covering the stoop below looked like a suitable catch basin. No one would be the wiser. With a quick flick of his right wrist, he dumped the tin.

“You, man, in the 15th Division, who just threw water out the window! Right now, hang your nob out!”

Oh, God! Tom thought, seized with terror. Slowly he reappeared in the window. An upperclassman, arms on his hips, stood directly below, elegantly dressed to meet his Saturday night date. Now that was spoony — all except for the tiny black flecks on his white hat and the shoulder of his white uniform shirt. Somehow the water had carried beyond the stoop and squarely spattered the cadet.

“What’s your name, mister?” the upperclassman demanded. “Sir, my name is Mr. Carhart.”

“Mr. Carter?”

“Sir, Mr. Carhart.”

“You have thirty seconds to get down here in six sets of sweats. Do you understand me?”

“Sir, if—”

“Six pairs of sweats in thirty seconds. Move!” “Yes, sir.”

Tom dashed frantically about the division, pleading with classmates to lend him their sweats. With each successive layer he moved more awkwardly. He couldn’t believe it: his resolve, his high-minded determination had come to nothing. This was going to be very unpleasant. A small group of upperclassmen gathered below, waiting to pounce. In the time-honored expression of the corps, Tom could “smell hell” as he waddled into the corridor toward the stairwell. Clearly, he was destined to suffer what cadets crudely described as the classic West Point experience: “a $50,000 education, shoved up the ass a nickel at a time.”

One afternoon during Beast, the cadre ordered the cadets into formation before herding them into South Auditorium. “Gentlemen,” an officer said as the lights dimmed, “General MacArthur spoke to us here several months ago and what he said was important.”

After a pause, a recording of the general’s voice, freighted with glory, thundered in the auditorium.

“Duty, honor, country. Those three hallowed words reverently dictate what you ought to be, what you can be, what you will be. They are your rallying points: to build courage when courage seems to fail; to regain faith when there seems to be little cause for faith; to create hope when hope becomes forlorn.”

The valedictory, which MacArthur had delivered in the mess hall on May 12, was the last performance by one of the nation’s greatest actors. He had prepared meticulously, memorizing the entire speech of more than two thousand words while pacing in a long robe through his tenroom apartment at the Waldorf-Astoria, puffing on his corncob as an Asian butler stood nearby with a tumbler of water.

He arrived at the academy gaunt from a recent bout with the flu. His hands, as veined as autumn leaves, trembled at lunch; perhaps to hide that palsy, MacArthur occasionally holstered them in his jacket pockets. He had combed his thinning hair from a part on the left directly across his crown, thus forming a perfect perpendicular with his hawkish nose. He was eighty-two years old.

“Your mission,” the general continued, “remains fixed, determined, inviolable — it is to win our wars. Everything else in your professional career is but corollary to this vital dedication. All other public purposes, all other public projects, all other public needs, great or small, will find others for their accomplishment; but you are the ones who are trained to fight. Yours is the profession of arms — the will to win, the sure knowledge that in war there is no substitute for victory; that if you lose, the nation will be destroyed; that the very object of your public service must be duty, honor, country.”

In language that admirers and detractors alike always described eponymously as MacArthuresque, he evoked West Point’s great heritage: “From your ranks come the great captains who hold the nation’s destiny in their hands the moment the war tocsin sounds. The long gray line has never failed us. Were you to do so, a million ghosts in olive drab, in brown khaki, in blue and gray, would rise from their white crosses thundering those magic words: duty, honor, country.

“The shadows are lengthening for me. The twilight is here,” he concluded. “Today marks my final roll call with you, but I want you to know that when I cross the river my last conscious thoughts will be of the corps, and the corps, and the corps.”

The new cadets, many with goose bumps, filed out silently, armed with a manifesto. If you lose, the nation will be destroyed. In the coming months they would hear the speech again and again. In their classes, in their barracks, in their sleep, they would hear the general’s call to arms.

Later, some would be troubled by the implication of West Point elitism; others would find the true Douglas MacArthur — solipsistic and often mendacious — to be less than the sum of his words. But for now he articulated an idealism that each of them had long felt. Amid the ordeal of Beast Barracks, the speech provided a vital and timely affirmation of a higher calling. The greatest of great captains had charged them with the fate of the nation. “The soldier, among all other men,” he had declared, “is required to practice the greatest act of religious training — sacrifice.”

They called him Saint Doug — and not in derision. They believed.

Three times a day, to the rapping cadence of a drum, the cadets marched through the oak doors of Washington Hall for meals. The enormous room had the ambience of a medieval mead hall. Portraits of past superintendents hung above the wainscoting, including a beardless, darkhaired Robert E. Lee, wearing a Union colonel’s uniform. A seventy-bythirty-foot mural covered the south wall, rendering more than two millennia of military exploits in a mass of spears, arrows, muskets, gas masks, siege engines, and elephants: Cyrus at Babylon, William at Hastings, Meade at Gettysburg, Joffre at the Marne. Above the main door of the mess hall perched a small balcony, known as the poop deck, which was reserved for distinguished diners; occasionally the cadets caught a glimpse of Superintendent Westmoreland at his private table, as godlike and elevated as Mars himself.

Nothing at West Point inspired more rituals than eating. After removing their hats at the foot of the mess hall steps, the cadets doubletimed to the tables, each of which seated ten. There they stood at attention until an upperclassmen gave the order to “take seats.” New cadets sat braced on the forward three inches of their chairs, eyes locked on the helmet of Pallas Athena embossed upon each plate.

A cadet ate each meal “squarely”: he cut off a piece of food no larger than a sugar cube and conveyed it to his mouth with a fork lifted from the plate and moved at right angles. Before chewing — as slowly and deliberately as a ruminant beast — the cadet returned his fork to the plate by the same route and placed his hands in his lap. Then he repeated the process.

One cadet at each table served as the “gunner.” He was responsible for ensuring that waiters kept the table supplied with food, dishes, and silverware. Those gunners who carved badly were ordered to the library to study Carving and Serving by Mrs. D. A. Lincoln, a volume requested so frequently that the special collections desk kept the book close at hand. Another cadet, designated the “coffee corporal,” was responsiblefor knowing the hot beverage preferences of upperclassmen and keeping their cups full. His cold beverage counterpart was the “water corporal.” Like everything else at West Point, meals had become an ordeal for the new cadets.

Perched on the forward three inches of his chair one August evening was a slender, rawboned nineteen-year-old from central Arkansas. His nose, broad and flat, had been broken five times when he played high school football. In photographs, his deep-set blue eyes often seemed widened with surprise. When he spoke, which he did as rarely as possible to avoid drawing fire from the upperclassmen, his words carried a thick drawl.

Like most of his classmates, George Allen Crocker was still hungry, even though the meal was nearly over. Unlike most of them, George Crocker rather enjoyed Beast Barracks. That came as something of a surprise: after a visit to the academy three years earlier, he had announced to his mother, “I wouldn’t go to that dumb school for anything.” Beast was not pleasant, and he certainly didn’t like the daily torment. But it was already clear that he had a knack for the military side of West Point — what little he’d seen of it — and the academy held for him the promise of a vocation.

“Crocker,” the table commandant barked, “what are you famous for?”

Answering this standard jibe was always delicate. Plebes who boasted of their high school accomplishments invited scornful sarcasm. As usual, George played it safe. “Sir,” he replied loudly, “nothing.”

Anonymity was one key to surviving Beast Barracks. George had witnessed — and often endured — the usual hazing, bracing, shower drills, clothing formations, and sundry acts of petty tyranny. The heaviest hand seemed to fall on those who stood out, either through singular ineptitude or a brassy reluctance to remain inconspicuous. New Cadet Crocker had tried to remain faceless, concentrating on the few enjoyable parts of Beast that helped to counterbalance the drudgery.

Marksmanship was one example. After the academy issued M-i drill rifles, the cadets used paper templates to learn the different parts of the rifle and how to field strip it properly. Gradually, they became proficient in the manual of arms — left shoulder, right shoulder, present arms. A cadet who referred to the weapon as a “gun” was rudely braced and told, in tones commonly reserved for misbehaving dogs, that a soldier never referred to his rifle as a “gun.” Then, alternately gripping his weapon and his genitals, he was forced to repeat fifty times: “This is my rifle. This is my gun. This is for shooting. This is for fun.”

Early in Beast, the class had jogged to a field near the river for bayonet instruction. “What’s the spirit of the bayonet?” the instructor demanded after teaching the horizontal and vertical butt stroke series, “TO KILL, SIR!” the cadets shrieked in reply before plunging their blades into the straw dummies.

Then came a week of “trainfire,” in which soldiers from the ioist Airborne taught them how to shoot M-14S. They learned to zero the sights, adjust for the wind, and keep the stock firmly against the shoulder to minimize recoil. The range offered a sequence of pop-up targets from 50 to 350 meters away. For long-range shooting, each rifleman had ten seconds to spot the target, tuck himself into position, and fire.

George had scored a 70, not the best marksmanship in his company but good enough to qualify him as an expert. A rifle felt comfortable in his hands. His father, William, was a superb hunter and had gradually worked his son up from a single-round .410 shotgun to a iz-gauge. They had often hunted ducks together in Arkansas out of a boat or a blind.

Bill Crocker came from Alabama, the oldest of ten children. In 1931, he was hired as a surveyor by Brehon B. Somervell, who later became the Army’s supply chief during World War II. The job was a godsend for a young man of limited education in the Depression, but when the nation mobilized for war, Bill tried to enlist in the Seabees. Medically rejected because of dangerously high blood pressure, he sat out the war at home — to his everlasting regret, particularly since his five younger brothers all joined the service. Bill continued to shuttle throughout the South as a construction engineer on dam projects for the Corps of Engineers.

In 1940, while working in Dardanelle, a small cotton town northwest of Little Rock, he met and married Adele Ellis, who worked in the box office of the Joy Theater. The daughter of a former soldier, Adele’s earliest memory was of standing near the Rio Grande and watching her father, George Jefferson Ellis, ride out of Mexico with his artillery battery after chasing Pancho Villa as part of Black Jack Pershing’s expeditionary force.

Bill and Adele Crocker continued to travel from dam to dam, wherever the corps needed Bill’s growing expertise: Alexandria and Monroe in Louisiana, Fort Smith and Dardanelle in Arkansas. In February 1943, Adele gave birth to a son, whom she named George, after her father. When Adele discovered that she could have no more children, Bill was relieved, so fearful was he of never being able to love another child as much as he loved George.

Dardanelle, with a population of about fifteen hundred, prided itself on being a town where everyone knew one another — and one another’s business — and where no one ever locked a door. Life for young George revolved around sports, hunting, the several newspaper routes that earned him a dollar a day, and the Arkansas River. In the mid 1950s, the Crockers moved to the bright lights of Fort Smith for a year; when they returned, George sported an Elvis Presley haircut, leather jacket, and boots. In time, they moved across the river to the bigger town and better schools of Russellville. George occasionally worked with Bill at the Dardanelle dam, which was being built to control the killing winter floods that periodically swept the bottomlands. He absorbed his father’s penchant for hard work and his unflagging honesty.

West Point was Bill’s idea. He admired the competence and commitment of the Army officers who came to work with him on the dam, and he could think of nothing finer than to have George become an academytrained engineer. George and a friend had entertained the notion of becoming dentists together; still, when Adele arranged an interview with a congressman she knew, George agreed to meet him. The congressman’s appointment to the class of 1965 was already filled, but he offered young Crocker the slot for ’66. Despite his earlier misgivings — “I wouldn’t go to that dumb school for anything” — George accepted. A free education was not something to refuse lightly, and the prospect of spending his life drilling teeth in central Arkansas no longer excited his imagination. Moreover, in the early 1960s the people of rural Arkansas accorded West Pointers something close to demigod status.

So, after a year at the University of Arkansas — where he joined the ROTC, pledged Sigma Nu, and partied relentlessly — George left for the Hudson highlands. His father drove him across Tennessee and up through Gatlinburg, following the Blue Ridge. At the Hotel Thayer on July 2,1962, before returning home, Bill offered his son parting counsel: “If you don’t make it, I’ll still be proud of you. And if you don’t like it, call me and I’ll come get you.”

George arrived as the latest levy of a type that had done very well in the American Army — the small-town Southerner. As recently as 1950, two thirds of the officer corps was drawn from farms or towns with fewer than twenty-five hundred people. In the South particularly, the values associated with physical prowess, service to the country, and social protocol still endured. There the notion persisted that for men who heard the calling, the military provided a fitting place to hone those values. In World War II, Arkansas among the forty-eight states had reputedly mustered into uniform more men per capita than any other; glory was not a word that made its citizens blush.

George was proud of that heritage, although he had found little glory in Beast Barracks. The past six weeks hadn’t been easy, but he knew now that he could survive the physical challenge of West Point. The academic challenge was another matter. In two weeks Beast would end and classes would begin. George had been a fair student at Russellville High, but the academy’s higher educational standards worried him. He was, as he later put it, “hoping for a miracle.”

Now, in the mess hall, the upperclassmen continued to distract the new cadets by demanding that they recite the arcana of “plebe knowledge.”

“Crocker,” the table commandant asked, “how many lights in Cullem Hall?”

“Three hundred and forty lights, sir.” “How many gallons in Lusk Reservoir?”

“Ninety point two million gallons, sir, when the water is flowing over the spillway.”

“How’s the cow?”

“Sir, she walks, she talks, she’s full of chalk, the lacteal fluid extracted from the female of the bovine species is highly prolific to the «th degree.”

The din of recitation resonated throughout Washington Hall. By this time, George and his classmates had been forced to memorize more than seven hundred lines of trivia.

“Sir,” bellowed another cadet, launching into “the Days” at an adjacent table, “today is Wednesday, 15 August 1962. There are two and a butt days until the weekend. There are 19 and a butt days until Labor Day. There are 76 and a butt days until Army beats the hell out of Navy in Philadelphia. There are 132 and a butt days until Christmas. There are 294 and a butt days until the class of 1963 graduates on June 5. The movie today is Two for the Seesaw with Miss Shirley MacLaine and, and — urn — Mr. Jack Lemmon.”

“Wrong,” the table commandant interrupted. “Robert Mitchum. Pass out your plate.”

The cadet surrendered his plate and watched wistfully as the waiter scraped the remainder of his pork chop, green beans, and strawberry shortcake into the garbage. In recent weeks, the authorities had halfheartedly tried to curb what was officially known as “food deprivation,” even staging surprise garbage weighings in an effort to detect which tables had unusual amounts of refuse. But the tactic rarely worked, because mess hall waiters usually tipped off the upperclassmen at the targeted tables. Since Beast began, George Crocker had lost twenty pounds; some of his classmates were beginning to resemble prisoners from Bataan.

Scrounging a few extra calories had become a passion. George’s room mate, Don Kievit of Canyon, Texas, had taken to swilling from a Lavoris bottle for the nutrition he fancied the mouthwash contained. Soon the entire ist Division was nipping away. Other cadets bloated themselves with water; if that didn’t quite quell the hunger pangs, at least it kept their stomachs from growling so ferociously. Still others ate toothpaste, or even sliced up the tongues of old shoes for something to chew.

Smuggling food from the mess hall was a venerable tradition. Cadets William T. Sherman and William Rosecrans, both destined to be Union generals, used to hide boiled potatoes in their handkerchiefs and stuff butter in their gloves, which they fastened beneath the table with fork tines until it was safe to retrieve the cache. But smugglers lived dangerously. Recently, one new cadet in the class of ’66 had been caught with a piece of chocolate cake under his raincoat. “You like cake, huh?” the upperclassmen asked. Procuring two whole cakes from the kitchen, they forced him to eat both while he double-timed through the barracks in poncho and helmet.

In letters from home, parents responded to their sons’ pleas by enclosing packets of Kool-Aid, flattened Tootsie Rolls, or any other “boodle” inconspicuous enough to escape detection. A few fretful mothers simply sprinkled the pages with sugar or cornbread crumbs. The cadets hid their boodle in laundry bags, nibbling furtively in the dead of night like a battalion of mice.

After supper, George and his classmates marched back to the barracks for the usual evening of brass polishing and harassment. At ten P.M., an upperclassman called out, “Smacks in the racks.” In the corridors of the ist Division, the so-called Wheelhouse, where many of West Point’s most illustrious sons — Douglas MacArthur, John Pershing, Charles Bonesteel, Jonathan Wainwright — had once lived, the squad leaders arrived for a newly imposed ritual. Having failed to thwart the starvation tactics through garbage weighings, the authorities had decreed that every night each new cadet would receive a half pint of milk and a piece of fruit. Grumbling about “coddled smacks,” the upperclassmen distributed an armful of bananas and apples. But George and the others couldn’t care less if they were coddled. For hundreds of them, this nightly feeding was the only thing staving off malnutrition. The bedtime fare also provided the class with its epigraph. The official class motto “Fame will mix with ’66” — had been replaced:

With fruit and milk we’ll get our kicks, For we’re the boys of ’66.

A bugler blew taps. As the final notes faded away, the barracks fell silent except for the soft rustling of a hungry cadet rummaging through his laundry bag, watched, no doubt, with amused detachment by the vigilant ghosts of the great captains.

Jack Wheeler paused outside the room of his squad leader, Jim Daly. Okay, he thought, here goes. He knocked sharply on the door and walked in.

“Sir, all that I am and all that I hope to be I owe to my squad leader, Mr. Daly,” Jack said loudly, braced at attention.

Daly looked up. His roommate was sipping a Coke with his nose buried in a book. The phonograph played “Scotch and Soda” by the Kingston Trio.

“Very good, Mr. Wheeler,” Daly said with a slight smile. “What else can we do for you?”

“Sir, request permission to make a statement.” “What is it?”

“Sir, I’m thinking of resigning.”

Daly’s roommate made an exaggerated gagging sound.