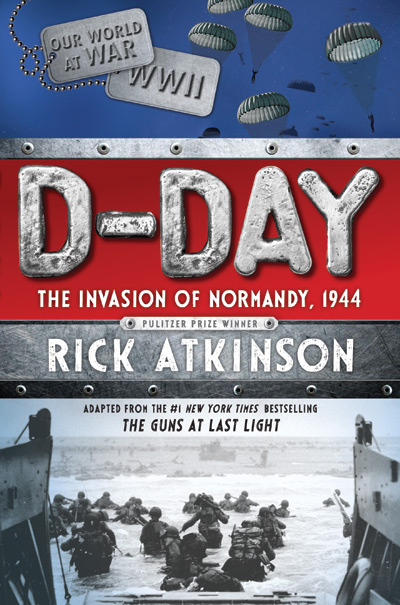

Excerpt from D-Day

You can download the first chapter of the book as a PDF file, or read below:

The Gathering

May 5, 1944

Allied command team behind D-Day (clockwise from top left): Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, Commander, U.S. First Army; Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, Naval Commander in Chief; Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, Air Commander in Chief; Lieutenant General Walter Bedell Smith, SHAEF Chief of Staff; General Sir Bernard Montgomery, Commander, 21st Army Group (all Allied land forces); General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander; Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder, Deputy Supreme Commander. February 1, 1944.

In this room, the greatest Anglo-American military leaders of World War II gathered to rehearse the deathblow intended to destroy Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. It was the 1,720th day of the war. Admirals, generals, field marshals, logisticians, and staff by the score climbed from their limousines and marched into a Gothic building of St. Paul’s School. American military policemen—known as Snowdrops for their white helmets, white pistol belts, white leggings, and white gloves—looked closely at the 146 engraved invitations and security passes distributed a month earlier. Then six uniformed ushers escorted the guests, later described as “big men with the air of fame about them,” into the Model Room, a cold auditorium with black columns and hard, narrow benches reputedly designed to keep young schoolboys awake. The students of St. Paul’s School had long been evacuated to rural England—German bombs had shattered seven hundred windows across the school’s campus.

An Air Scout, a subgroup of the Boy Scouts, draws a picture of a Spitfire fighter plane for a group of other Air Scouts to learn aircraft recognition as they sit on the lawn of the evacuated St. Paul’s School.

Top-secret charts and maps now lined the Model Room. Since January, the school had served as headquarters for the British 21st Army Group, and here the detailed planning for Operation overlord, the Allied invasion of France, had gelled. As the senior officers found their benches in rows B through J, some spread blankets across their laps or cinched their overcoats against the chill. Row A, fourteen armchairs arranged elbow to elbow, was reserved for the highest of the mighty, and now these men began to take their seats. The prime minister of England, Winston Churchill, dressed in a black coat and holding his usual Havana cigar, entered with U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, whose title, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, signaled his leadership over all of the Allied forces in Europe. Neither cheers nor applause greeted them, but the assembly stood as one when King George VI strolled down the aisle to sit on Eisenhower’s right. Churchill bowed to his monarch, then resumed puffing his cigar.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Sholto Douglass (left) standing with his senior air staff officer in the operations room on the morning of the invasion.

As they waited to begin at the stroke of ten a.m., these big men with their air of importance had reason to rejoice in their joint victories and to hope for greater victories still to come in this war.

His Imperial Majesty King George VI

Since September 1939, war had raged across Europe, eventually spreading to North Africa and as far east as Moscow, capital of the Soviet Union. Germany, a country humiliated after World War I, had seen the rise of Adolf Hitler, a dictator who had dreams of conquering the continent. Beginning with Poland, his armies had crushed one nation after another, destroying cities and killing or enslaving millions of people. His collaborators in the Axis alliance, particularly Japan and Italy, pushed their own campaigns of aggression in Asia and Africa.

Sir Winston Churchill, prime minister of the United Kingdom, inspecting a crater left by a German bomb in London, September 10, 1940.

Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, and Japan’s attack in December of that year on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, led to a grand alliance determined to stop the Axis. The United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union were the major Allied powers, but they were supported by dozens of other countries. At an enormous cost in blood, Soviet armies pushed the German invaders back through eastern Europe, mile by mile. German casualties there exceeded three million, and in 1944 nearly two-thirds of Hitler’s combat power remained tied up in the east.

Adolf Hitler, führer of the Nazi Party (right), and Benito Mussolini, prime minister of Italy, in Munich, Germany, June 1940.

The United States and Britain, meanwhile, had defeated German and Italian forces in North Africa. They then moved north across the Mediterranean Sea to conquer much of Italy, which surrendered and abandoned the Axis. The Third Reich, as Hitler called his empire, was ever more vulnerable to air attack. Allied planes flying from Britain, Italy, and Africa dropped thousands of tons of bombs on Germany and on German forces along various battle fronts. City by city, factory by factory, Germany was a country increasingly in flames. Although they paid a staggering cost in airplanes and flight crews, the U.S. Army Air Forces, Britain’s Royal Air Force, and the Canadian Air Force had won mastery of the European skies, even as Allied navies controlled the seas.

The U.S.S. Shaw explodes during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941.

By the late spring of 1944, the Allies were ready to attempt something that had long seemed impossible: to invade what the Germans called “Fortress Europe” and begin the final campaign that would free citizens who had been enslaved since Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. The hour of liberation had nearly arrived.

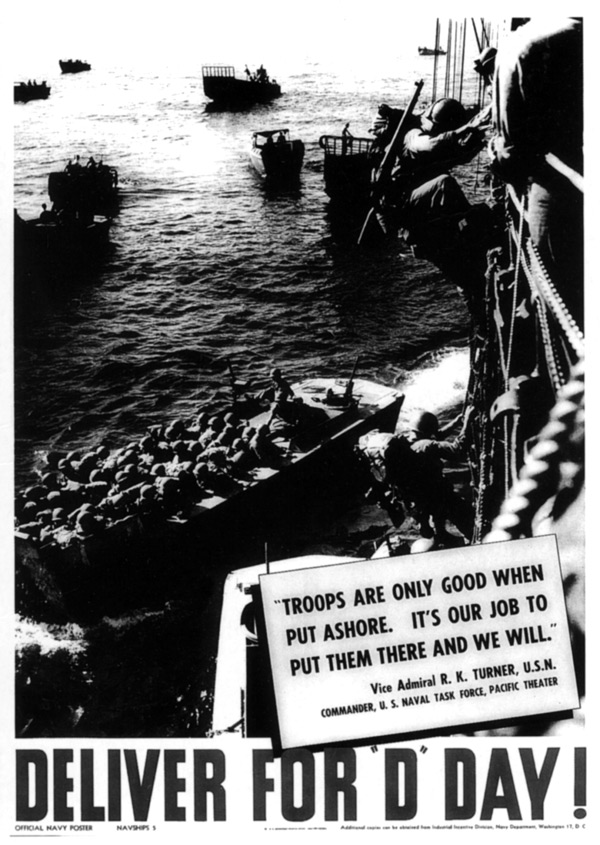

A U.S. propaganda poster encourages increased production prior to D-Day, 1943–1944.

Copyright © 2014 by Rick Atkinson